Words by Emma Frith

Despite its career defining performances, intimate shots and clever use of colour, the award-winning french film Blue Is the Warmest Colour unfortunately fed into a larger problem of representation within queer cinema.

Many films that depict lesbian relationships are directed by men (eg. Disobedience, Carol, Ammonite) and although this is not always a problem, it is extremely noticeable in Blue Is the Warmest Colour, in the worst possible way. The pervasiveness of the straight, male gaze imposed so heavily on a film aimed at depicting passionate love between two women does not go unnoticed by a queer audience: straight men directing lengthy, relatively impassionate sex scenes and a relationship that lacks communication and even chemistry at times does not serve the queer community. Rather, it adds blue coloured fuel to a filmic fire being kept alive by poor representation.

The creator of the original comic book described the film adaptation as “a brutal and surgical display, exuberant and cold, of so-called lesbian sex”. This negative commentary aligns with actress Léa Seydoux’s lived experience on set: when asked if she felt that she was perpetuating a male fantasy, she answered “Yes. Of course it was kind of humiliating.”

Unfortunately, Blue is the Warmest Colour continues to be a staple piece of lesbian cinema, but not for a queer audience. Considerably better representation is out there, and luckily is becoming increasingly more common. Here are our picks for our queer foreign films that offer a less harmful, more honest image of queer love…

Happy Together is as much a story of love as it is of loneliness and distrust. Wong Kar-wai’s 1997 film focuses on two men who undoubtedly love one another, but in such contrasting ways that they might as well be in different time zones. For one, love is climbing into his bed, annoying him until he lets you stay. For the other, love is buying him cigarettes, so he never has a reason to leave you ever again. For them both, it’s slow dancing in an empty kitchen together or standing at the edge of a waterfall hand in hand.

We follow Lai Yiu-fai, a man who drifts between jobs in a bustling Buenos Aires. His part-lover-part-enemy-but-only-constant Ho Po-wing is a cocky and easily bored troublemaker, who shows up at Yiu-fai’s door with bloody fists and a bruised face after previously leaving him high and dry on what was meant to be a trip across the globe together. What follows is a rollercoaster of emotions; jealousy which leads to fighting and yelling, which then leads to tenderness, which then leads back to fighting, and so the cycle continues.

Happy Together teaches us that sometimes in order to be truly happy together, you have to take some time apart. Sometimes you both realise that you don’t truly like each other that much; but maybe this doesn’t mean that you could ever see yourself loving anyone else either. Sometimes real love is not about being with someone, but not being able to be without them.

With black and white sequences contrasted against scenes bursting with warm colours and evening lights, Happy Together, is a beautiful and tender piece of queer cinema centred around characters with great depth that resonate and linger with you long after watching.

Of Love & Law – Daisy H.

Of Love & Law is a charming 2017 documentary from Hikaru Toda which follows Fumi and Kazu, the first openly gay couple to open a law firm in Japan as they attempt to eradicate the fear and ostracization of the ‘Other’ in a society where laws protecting minorities in regard to race or sexuality are non-existent.

Toda seamlessly blends together the personal and political struggles faced by minorities in Japan, in both a societal and structural capacity, with emotional accounts of Fumi and Kazu’s family and clients alike, whilst simultaneously educating the audience about Japan’s legal system and the wider cultural attitudes that shape it.

Exploring the devastating effects Japan’s homogenous societal culture has had on minorities, and the archaic legal system that exists behind it, we are given insight into the Japanese legal system through some of Fumi and Kazu’s cases. This includes an artist on trial for obscenity due to her vagina-shaped artwork, a teacher appealing a recent termination after refusing to sing the national anthem, and individuals who cannot gain full recognition as citizens due to issues like being born out of wedlock, childhood neglect, or fleeing domestic violence.

Despite the heavy, subject matter, Toda succeeds in delivering it in a light, heart-warming and humorous manner. Through the delightful and authentic Fumi and Kazu, and the intimate detailing of their lives and shared love, we are left with a beautiful portrait of the duo’s experiences as LGBTQ+ individuals, as well as a wider commentary on Japanese society, resulting in a documentary that is equally educational and endearing.

Funeral Parade of Roses – Emma Norris

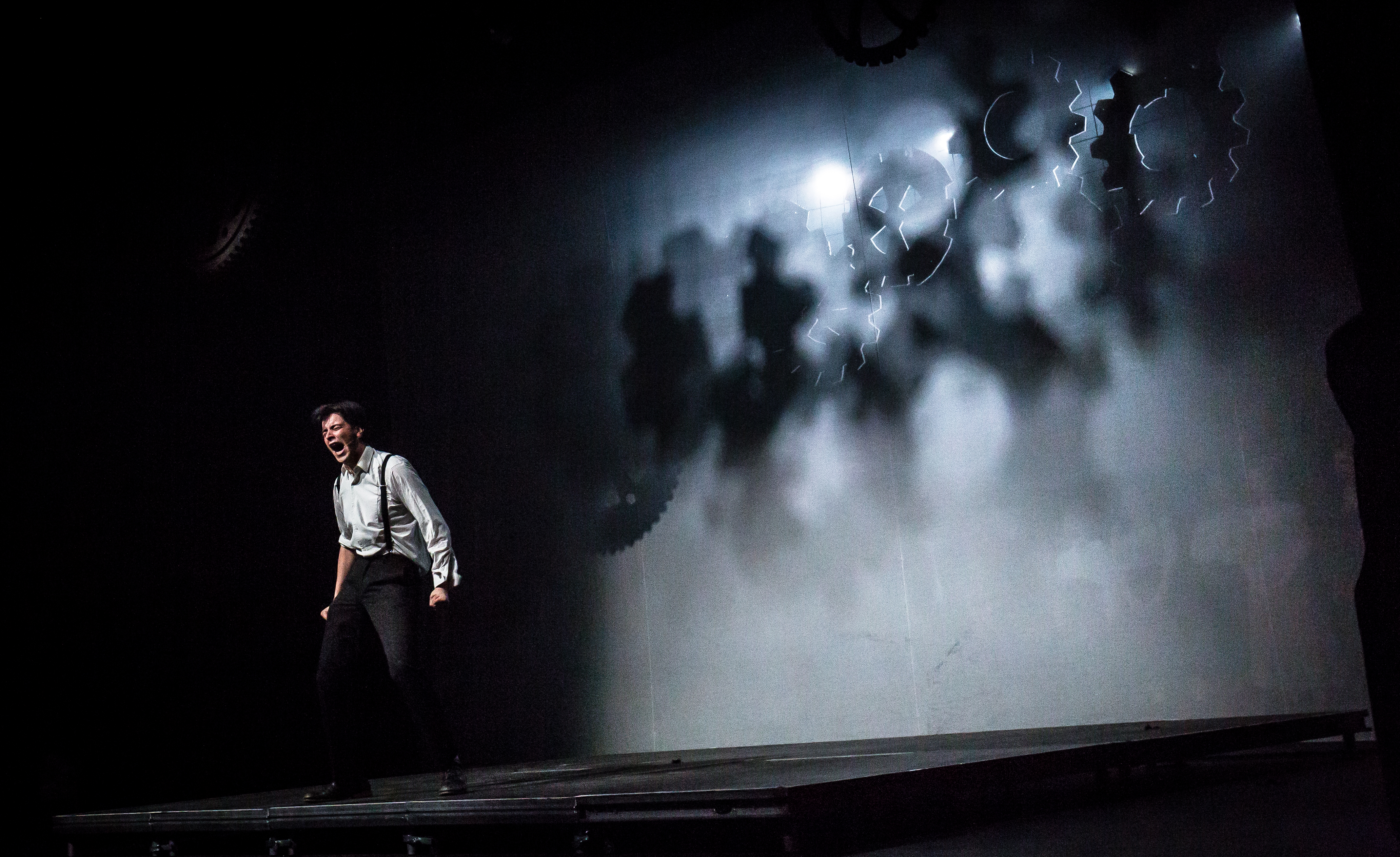

Combining elements of documentary, arthouse and experimental theatre, Funeral Parade of Roses offers us an utterly enchanting and dazzling insight into the gay scene of 1960s Tokyo. Released in 1969, the film follows protagonist Eddie through their life, struggles and joys, living as an LGBTQ+ person in an era in which, to live true to this identity, served as an act of bravery and defiance against societal norms and expectations. The film artfully combines elements of drama, romance and documentary to create an energy that is unique, experimental and exciting, offering the viewer an authentic insight into LGBTQ+ culture that is so rare for this time period. What is most significant about this film is its placing of the trans experience at the forefront, refusing to shy away from the experiences of a minority that are so often overlooked or misrepresented.

The film focuses on the lives and apparent rivalry between Eddie and Leda, the Madame of an underground gay bar, detailing a bitter feud between the two over a complex love triangle that ultimately descends into chaos and tragedy. Intertwined into this drama are clips from interviews with trans people, who answer questions about life living as an LGBTQ+ person in a time when this was widely kept in secret and confined to the underground scene of central Tokyo. The film is thought to have inspired Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of A Clockwork Orange and serves as a landmark in the growth of LGBTQ+ culture in mainstream discussion and entertainment.

Beau Travail (1999) – dir. Claire Denis

Rob Salusbury

Relocating Herman Melville’s legendary unfinished novella Billy Budd to the sweltering desert heat of Djibouti, Claire Denis’ 1999 film Beau Travail is an enthralling, hazy tale of jealousy and desire. Following a group of French Foreign Legion soldiers led by Sergeant Galoup (Denis Lavant) as they carry out intense physical exercises and stalk through the local towns and nightclubs, Denis gradually deconstructs the strictly-regimented order of the group to reveal a deep core of unrequited passion and bitterness.

Narrated in the present day by Galoup as he reflects back on his time with the Legion, we learn of his repressed desires for his superior officer Bruno Forestier (Michel Subor) and the threat he feels when a confident young soldier, Gilles Sentain (Grégoire Colin), joins the group. As we are drawn into Galoup’s paranoid, hazy memories of this triangle of lust, the tension swells within the group.

What really elevates this intriguing tale of male desire and anger is Denis and cinematographer Agnès Godard’s almost impressionistic style of filming that feels at once both light as a feather and impossibly intoxicating. The camera floats between the shirtless, glistening bodies of the soldiers and then suddenly flits away into the golden sand dunes of the desert and the dull lights of the nightclub, lending the whole experience a hallucinogenic air that strengthens the heady cocktail of emotions Galoup is wrestling with.