In 2005 economist Steven Levitt and New York Times journo, Stephen Dubner, debuted Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything. At first impression it sounded very much like Economy For Dummies, a watered down account of how the economy ‘works’ and the peculiars of finance. But it ended up being far more than just that. It took basic and non-basic economic principles and applied them to concrete situations, such as in chapter five: ‘The negligible effects of good parenting on education’. The book particularly uncovered criminality in detail, like in chapter three’s ‘The economics of drug dealing, including the surprisingly low earnings and abject working conditions of crack cocaine dealers’ and chapter two’s ‘Information control as applied to the Ku Klux Klan and real-estate agents’. The book took a sociological approach to economics, raising much criticism and acclaim for the section on how legalized abortion impacted crime, Levitt’s argument being that it’s reduced almost half of criminality witnessed throughout the ‘90s. It’s safe to say that Freakonomics became one of the most popular non-fiction economics book read by lay-people and professors alike, selling over four million copies worldwide by the early 2000s.

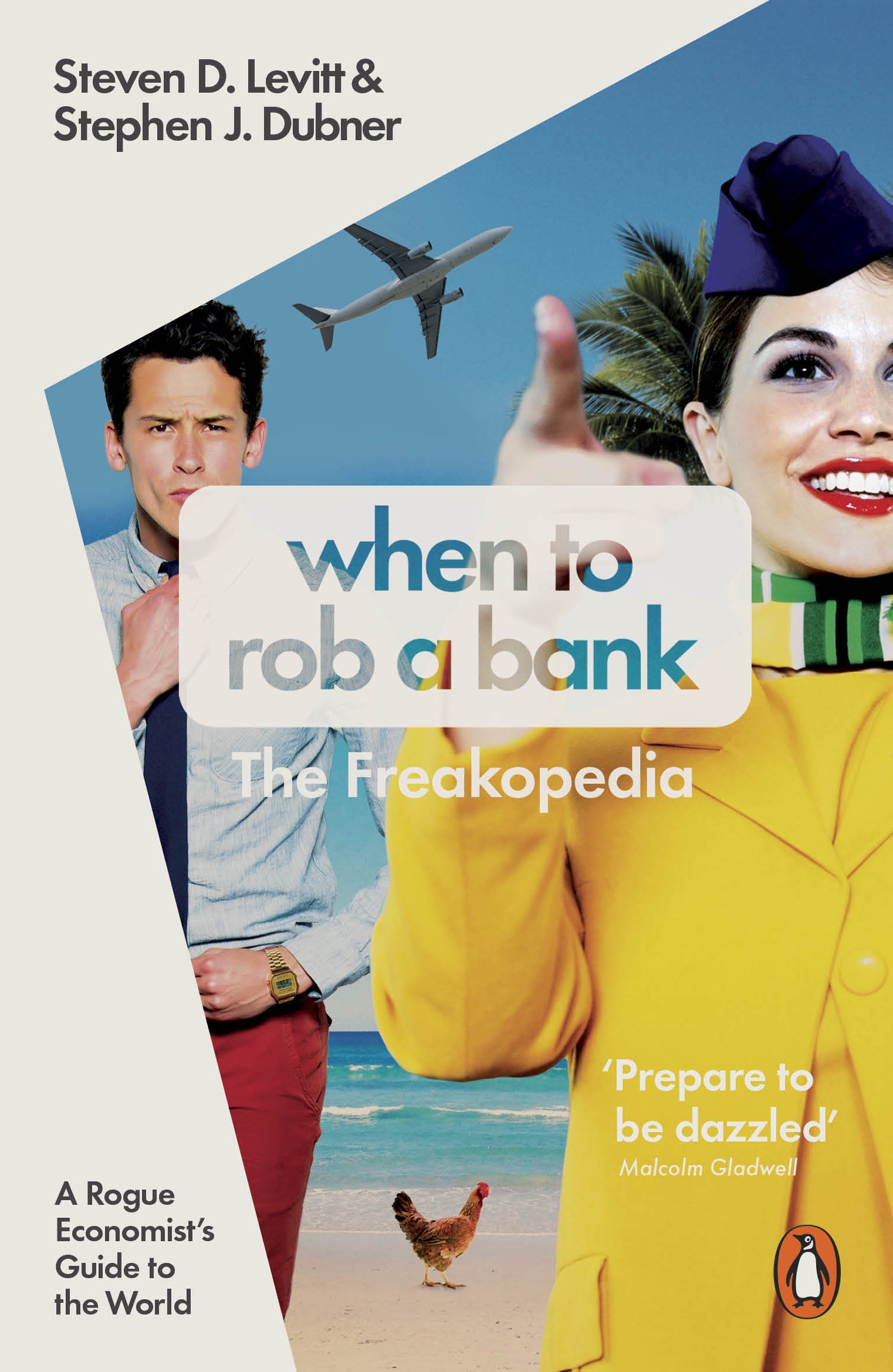

Since then the duo have written Super Freakonomics: Global Cooling, Patriotic Prostitutes and why Suicide Bombers Should Buy Life Insurance; Think Like a Freak and lately, When To Rob A Bank. The Douglas Adams-esque titles give us a little insight on what content to expect, odd and somewhat funny accounts of applied economics, and the latest installation doesn’t disappoint. Written in the personal/ quasi-essay style that has allowed for the other editions to have gained such wide readership, one chapter accounting a night out in Vegas, ‘So Levitt and I were in Las Vegas this weekend, doing some research. (Seriously: it’s for a Times column on Super Bowl gambling). We had a little downtime and decided to play blackjack’. Consistently told in the present tense, the story follows various life experiences of the writers, with their initials at the top of every story. They give us a very real understanding of how economic principles work, how they can be applied to every day life, they almost make it seem easy.

But alas, it’s not easy, the story illustrates a friend of Levitt’s, Brandon Adams, who the authors refers to as one of the best poker players in the world (and a great writer as well, apparently), who ‘makes so much money playing poker that he will likely never finish his economics Ph.D at Harvard’. The book possibly insinuates the evils of gambling and the ‘classic example of opportunity cost’ (what investopedia.com describes as ‘an opportunity cost refers to a benefit that a person could have received, but gave up, to take another course of action’). Levitt beats Adams and makes it to the next table, the book goes on to describe a blackjack round that has Levitt at 82% chance of winning the right hand, and if he had, he would have had 90% of the chips, making it impossible not to get into the final table. Yet, he looses, ‘the Cinderella story had come to an end. I was out’. The chapter highlights well-known tales of gambling, we all know that the house always wins, but to what extent? Well, if Levitt, a UChicago economist couldn’t win, then who does? One might just imagine it was all down to luck. The book is filled with these kind of stories, my personal favourite being ‘More Sex Please, We’re Economists’, which starts with a story by Dubner: ‘Breaking News: Soccer Fans Not As Horny as Previously Thought’. It gives an informative account, in bullet points among prose, of a Sex Tax. Whether you study economics or just want handy (although at times dubiously useful) food for thought, do have a read. It’s funnier then you’d imagine, plus I know you want to know ‘bout the Sex Tax.