Words by Rosie Graham

Let’s be honest, summer 2020 wasn’t exactly one for the books. Staycations, zoom quizzes and socially-distanced picnics came to embody the pandemic summer. For seasonal workers, however, the virus introduced a whole new set of challenges. A group of Sussex students, including myself, struggled with the uncertainty of our jobs abroad at a members’ club on the Greek island of Zakynthos, and witnessed the virus’ impact upon the tourism industry first-hand.

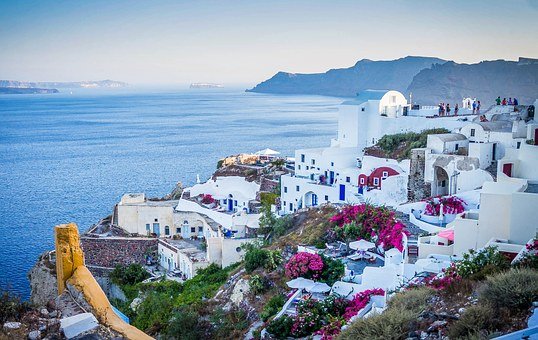

The traditional Greek summer season begins mid-May, as temperatures rise to a steady 25 degrees and higher. The clear blue waters, beautiful weather, dramatic scenery and plush greenery usually draw half a million Brits to the island each year. The tourism industry, therefore, is central to the economy of the Ionian islands, accounting for up to 10% of employment. Many mainland Greeks living in the bigger cities head to the islands for the summer season, benefitting from reliable income. Similarly, British seasonal workers (or ‘seasonnaires’) head out to the islands to join the tourism community, usually working for British-based tour operators such as TUI or Thomas Cook.

This May, however, the UK was barely emerging from a heavy lockdown, and chances of getting on a flight looked slim with intense travel restrictions. The price of international flights soared, airports turned into ghost towns, and the future of travel looked weary. Even if, at some point in the distant future, travel restrictions did permit holiday-making, would anybody risk it? Would there be any need for my job? I buckled up for a long summer living with my parents and applied to literally any supermarket hiring, giving up hope of another Mamma Mia summer.

Being UK-based themselves, our employers were as unsure and hesitant as everyone else. They assured us that our summer would be going ahead, albeit with a dramatically reinvented programme to adhere to both Greek and British guidelines and delayed start dates, and that they had considerable interest from customers. As the UK began to open up restaurants, bars and non-essential shops, there was a glimmer of hope. I turned on all alerts for flights to Greece from my local Manchester airport, anything under £100, and hoped for the best. Tilly, an American Studies student at Sussex, comments “my biggest worry was job security, because every week or so we’d have a new update and more speculation, and never clear enough guidance to indicate what was actual going to happen or how our jobs would be affected by the progression of the pandemic.”

After an eternity of waiting, pushed back start dates, cancelled flights; everything happened so quickly. We were told the club was to open July 4th, with staff being sent out in batches throughout the month. I received a phone call from recruitment confirming my flight details on the Saturday afternoon and was shipped out to Greece within 12 hours.

From the moment I landed I knew it was going to be a radically different summer than the ones I had enjoyed so enthusiastically in previous years. What would normally be a heaving airport, buzzing with excited tourists, was replaced with only a small crowd and a solemn queue for a randomised COVID test. Just as I was starting to feel anxious, I was met with a Greek doctor brimming with cheeky humour and a friendly nature – just what I had remembered.

Our first few weeks at the club saw few guests. With a capacity of around 400 guests and 120 staff, we had 50 guests and around 60 staff – a considerable difference. We wore masks 24/7, sanitised our hands between every interaction and temperature checked all people coming in and out of the club. With such little staff, the work was hard. Long hours in extreme heat is taxing, regardless of intense safety procedures. Whilst I thought these measures would be destructive to our peaceful, relaxing holiday environment, guests seemed so thrilled to be abroad that they didn’t mind and were happy to cooperate. Initially, guests were from Europe or the US, but as the UK introduced the air bridges initiative, business boomed. We went from 70 guests week 2 to 380 on week 3. Being that the club is mostly outside, and naturally socially distanced, it was an opportune place to visit in a pandemic.

The rural location of the club was vital in creating a COVID-safe bubble for staff and guests. The small port of Agios Nikolaos on the north coast of the island contains around four family-run restaurants and two small convenience stores, thus little opportunity for the spread of COVID – the antithesis of the British experience. Often, when visiting these local restaurants and bars I would ask owners how their season had been with COVID. Every time, without fail, I was met with sad smiles, “not good” they said.

The impact of the pandemic upon the island’s tourism was obvious. Even our small local port, that barely saw guests external to the club, was tainted with an undertone of worry and hesitancy. Greek police were committed to monitoring COVID measures in hospitality, all too aware that one small slip up could introduce an outbreak that would in turn shut the island to tourism and prove detrimental to the already struggling economy. The Greek guidelines were confusing and continued to evolve as the situation progressed. We heard stories of bars in the city fined €10,000 for having people stood at the bar, or venues shut down for inadequate regulations. For Will, a student at Nottingham University, “the most challenging part was the uncertainty of what was happening with local governments in the region. With the club having to abide by both UK and Greek law, it all became a bit of a mess.”

As the world anticipated a ‘second wave’ as summer came to a close, ever changing regulations left us paranoid and anxious. The “mess” that Will’s referring to came all too soon as Boris Johnson implemented a two week quarantine upon return from several Greek islands, including Zakynthos. I started my shift at 4pm, and by 10pm had a last-minute flight booked for the next day in order to make it back to the UK in time for the start of the university term. Pip, a masters student who did her undergrad at Sussex, said her biggest stress was “getting stuck out in Greece and not being able to return home for uni in time.” Landing back in Heathrow this September after two months abroad, with such short notice, was surreal. Pip confirms “I had the most phenomenal summer regardless of everything going on around us.”

Enveloped in anxiety, stress and ambiguity, our summer of 2020 was, surprisingly, unforgettable. There’s no denying that whilst the regulations and measures surrounding the pandemic made our jobs infinitely harder and less secure, but considering the summer I could’ve had at home, I’m so grateful I was able to return to Greece. After all, a pandemic doesn’t look so bad with an Aperol Spritz in hand.

[…] Working abroad through a global pandemic […]