Words by Ellie Massey Howes

36% of all grades released on 13 August were lower than teacher predictions, resulting in the loss of university places for many, and sparking huge outrage amongst students, parents and teachers.

So, what happened? Ofqual – the Office of Qualifications and Examinations – developed an algorithm through which a student’s centre-assessed grades (based on teacher predictions and a student’s ranking compared to other pupils in that grade) were analysed. This algorithm then factored in a school’s performance over the previous three years for each subject to determine the final grades for each student.

The intent was to ensure that grade inflation would not catalyse adverse effects on universities nationwide. This followed concerns raised around potential oversubscription of student finance, course and student accommodation, and the impact of what rewarding a higher number top-class grade classifications (based on teacher predicted grades) would do to the future job market in lieu of students taking official examinations.

There were concerns that university finances would suffer in terms of elevated cohort sizes, as some institutions were predicted to have a larger intake than planned due to more top grades being awarded. Adversely, others could end up with a lower intake than foreseen, with prospective students potentially being accepted into rival, higher-ranking institutions.

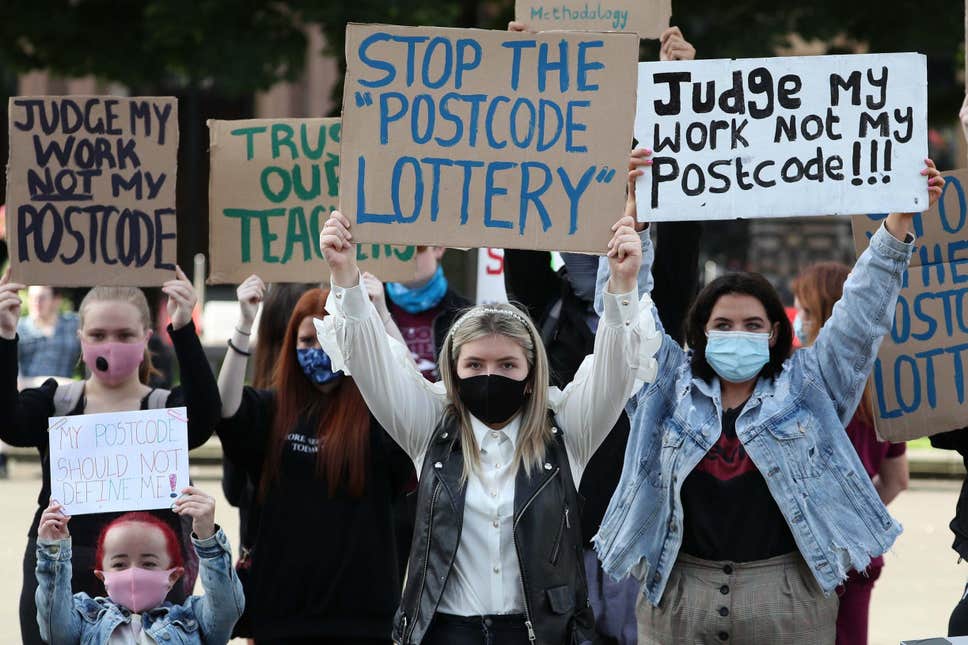

A major issue with the downgraded results for pupils and schools nationwide has been that it has increasingly affected students from underperforming schools – with bright pupils in these schools being downgraded one to three grades lower than what teachers had assessed.

Schools who had been statistically improving would not see their achievements reflected in this year’s results either, as the Ofqual algorithm took into account the historical academic performance of each school when deliberating grades.

This year’s A-Level grading was, therefore, more likely to disadvantage already marginalised high school students. Factors such as family income inequality and socioeconomic status, lack of regional state school support and funding, and educational attainment gaps affecting ethnic minority groups lead to secondary schools in more deprived socio-economic areas performing worse than institutions in advantageously prosperous regions.

Similarly, the proportion of top grades increased the most for private schools, with 48.6% of pupils at independent schools getting an A or A* grade – double the percentage point increase of secondary comprehensives.

The algorithm has further undermined the concept of a meritocratic education system that promotes social mobility and has exposed inequalities already at play within the UK.

Studies show that pupils from a disadvantaged socio-economic background are on average 18 months behind their peers by the age of 16.

Andy Burnham, Mayor of Greater Manchester, said to BBC News that he was “fully prepared to take legal action” against Ofqual’s “straightforwardly discriminatory” grading system.

“It discriminates against young people on the basis of the institution that they went to, rather than their ability,” he said. “It is clear to me that the system used to mark A-Levels is inherently biased against larger educational institutions,” with bigger, urban sixth form colleges being attended by larger numbers of working-class and ethnic minority student populations.

Initially, Education Secretary Gavin Williamson defended this algorithm as “fair,” and Ofqual Deputy Chief Regulator and Executive Director for Strategy Risk and Research Dr Michelle Meadows commented that analysis of the assessment model showed “no evidence of systematic bias.”

However, student protests following the A-Level results announcement resulted in a U-turn from the devolved governments of England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. It was instead announced that the original centre-assessed grades (the ones based on teacher predictions) would be awarded instead.

But how has this all affected this year’s cohort of new university students? After many rushing through clearing after being rejected from their original university choices, some are now being told that even with downgraded results being upgraded to the centre-assessed grades, there is no place for them on the course or at their desired institution.

Some universities have responded by incentivising students to defer their entry to receive a place on their first-choice course. Universities are urging the government to guarantee funding to maintain the capacity of students they will be receiving this year.

The University of Sussex Students’ Union accused Ofqual’s algorithm delegating A-Level results this year as providing results that “favour those who were already favoured by the education system,” and offered solidarity to all students who may have been affected by the measures.

In light of the grading and algorithm upset, Sally Collier, former Chief Regulator at Ofqual, has resigned. Dame Glenys Stacey, the previous chief, has since reoccupied the position.

Despite the emerging clarification over the past weeks, the long-term ramifications of this controversy remain to be seen.