As writers for a student publication, we are often wont to demonstrate a literary prowess. The desire to flex some scholarly muscle often floats through in the discussions around literature featured in this paper. Whether through championing woke novels, long-forgotten gems, or an insurmountable epic, what often persists – in every student book club – is a degree of isolationism, to seem unique.

The shame of this is that writers are left segregated from their readers. Pomp is essential, and necessary to the development of literature, but there are reasons to propose that one’s literary prejudices are reigned in on occasion. High culture can sometimes tip into the kitsch, and beside isolating one from the opinions of their peers, it aids in something far more catastrophic – a reluctance in others to read.

Poetry is an excellent example of a form that, due to its pomp, isolates its public. Beat poetry and slam are forms with a self-effacement so severe that audiences are put off, cutting the cash-flow and starving the medium. This comes a hundred years after Wordsworth’s Preface to Lyrical Ballads argued that poetry simplify in order to capture the imagination of everyone, not just a literati.

My attack on pretension comes in order to validate my following point, which draws criticism not just from the hyper-literate, but from non-readers too; children’s books make the perfect Autumn read, especially for University students. Now, for my defense.

I suspect our reticence towards children’s books comes from a sort of shame instilled in our primary school years. The rate of acceleration in reading age is fast when we are young, only slowing when reading is no longer enforced. However, the years prior to this, we are made to jump from the Alphabet to The Hungry Caterpillar, to We’re Going on Bear Hunt, to Roald Dahl, and then Harry Potter, with impressive speed. If one is not meeting their school’s reading targets a degree of shame falls upon them. Sometimes this shame hardens into a resolve, a resolve not to read at all. For those that progress, the shame centered around “easier” books persists, meaning children’s books are all too easily looked down upon. We may remember the texts with fondness, but we’re embarrassed to revisit them.

If one were to openly admit their reading of children’s books, I expect derision would only be met with in a social context, with jest. Every one of us has a fondness for a particular book from our childhood, whether by adaptation or the exploration of the initial text, and in a nice environment we’ll admit to the fact. Whether we will find an actual copy and spend our time with it, then, is more unlikely.

A children’s book offers a world of simplicity that literature tends to scorn. As “educated readers” we are expected to see a text as an exercise in semiotics, or a grand code. We are to look to it as something to deconstruct and contextualize in a way that fits a particular theory. We speak of it with a vocabulary, our enjoyment becomes Marxist, Hegelian, Kafka-esque; but is this necessary?

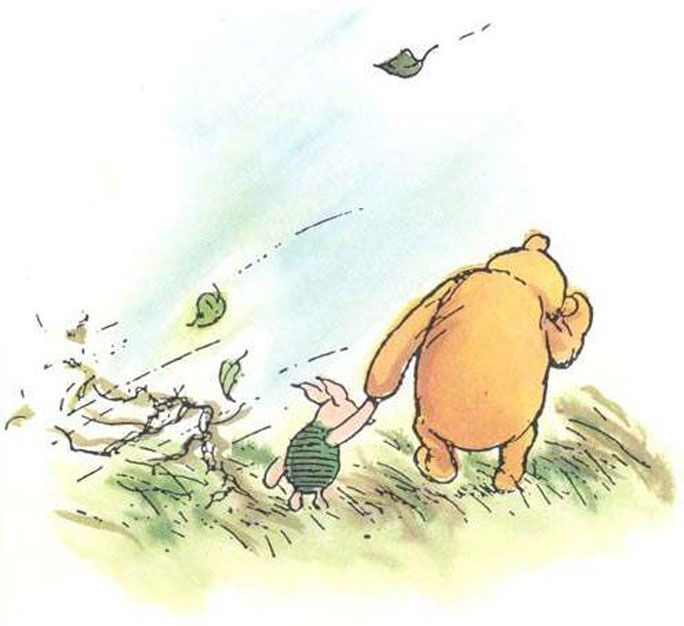

Perhaps, in a particular context. There is every excuse for psychoanalysing the inhabitants of the Hundred Acre Wood if such an analysis could be used in an educational context, or as a coping mechanism when confronted with particular issues. A colonial reading of The Jungle Book may be a useful in illustrating the linguistic imperialism at work in the late-eighteen hundreds. However, to undertake a book with the notion of conducting a reading is not essential if one’s primary desire is to enjoy themselves, to waste time, to marvel.

Children’s literature is excellent due to the worlds they create. Flying children and magic chocolate factories do not find their ways so easily into adult literature without an undercurrent of explanation. In children’s books, things happen because they do, issues are resolved because they are. To inquire further is not one’s duty, as it is not the child’s.

Books such as The Magic Faraway Tree and Alice’s Adventure’s in Wonderland, while full of events and signs that may represent, are far more rudimentary in their use of language than, perhaps, an adult book could be. The notion that a parent may be performing the text for their child is at work throughout each sentence, meaning there is a level of aestheticism at work, a construction that ensures the derivation of pleasure from the arrangement of words, their sound, the image they conjure, with very little underlying. To resign oneself to surface meaning, to enjoy the image, is a thing cast aside in the politicised world of the campus. Whatever text one is assigned to read, power-relations, symbolism, and history are at play to ensure one is enlightened by the text, and can make use of it in an academic setting. As exams loom and these texts mount, I would recommend that students – at least for a moment in their week – turn to a text such as Harry Potter, or Peter Pan and take a moment to enjoy the shape of the sentence, the sound it makes. By banishing the notion that the text may be brought up in an academic realm, we may all be able to choose a text and keep it as something apolitical, that bestows pleasure for something intangible, for something personal.

I expect, for many, the ephemeral joy they find in their chosen children’s text will be its connection with another world. The passage it offers back to a cosy bed against their parent’s shoulder, to a quiet moment in a classroom, to their discovery of joy elicited from words on a page, will attract them. In many ways, reading children’s books is an act of mindfulness, a meditation, it is a reminder to be present and calm, to not worry. While we are encouraged, against the facade of an election, strikes, and exams, to be angry, anger should be reserved for what deserves it. The children’s book you choose, for a time, should not.