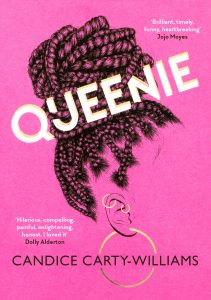

Candice-Carty Williams is set to feature at Brighton Festival’s event Shapeshifters on 12 May alongside the equally talented Zawe Ashton. She will be discussing her brand new book, Queenie, which is set to come out on 11 April. It tackles numerous themes, including dating, therapy, race and family, and follows the story of Queenie Jenkins, a 25-year-old Jamaican British woman living in London and working at a national newspaper. With another book also in the pipeline, there will be plenty of opportunities to read her fiction in the near future.

We got the chance to catch up with Candice and talk about everything from her personal experiences, her career generally and her new book.

You will be speaking at Brighton Festival’s event Shapeshifters alongside Zawe Ashton. How did this collaboration come about?

When I started working at Vintage two and a half years ago I was looking through the author folders and saw Zawe’s name and was beside myself with excitement because I’d loved her as an actor and poet for such a long time. So I worked on her book, Character Breakdown, and forced her to be my friend, and now she’s one of the main women that I love and trust who empower me and my work. We’ve both worked at some point with Nii Parkes, the festival’s programmer, and when he suggested throwing us together because he knew it would work, we both immediately said yes!

The event is very aptly named Shapeshifters, what have been your experiences having to ‘shapeshift’ or ‘codeswitch’ in your career?

Working in publishing, I had to do it constantly when I first started out. I’ve never worked with a permanent member of staff like me before, and weirdly I thought that sounding like myself would be the only thing to make me stand out. Now, I only actively codeswitch if I need an Alexa to listen to me.

So what do you want your readers to take from your talk at Brighton Festival? What is the important message you hope to give?

Mainly that us Shapeshifters are everywhere, and that it’s basically a whole job (alongside existing day to day) as well as our actual jobs. But it’s also going to be a really interesting look at two different narrative and lenses, across fiction and memoir!

And the novel that you will be talking about at the event is Queenie, which is due to come out on 11 April. What was your creative process when writing the novel?

I only write at night, so after completing a huge chunk of it at Jojo Moyes’s writing retreat, I spent literally every weekend, Friday after work to Monday morning, locked in my gross studio flat writing in bed. Writing really was my escape. Once I’d written the first draft, I sent it to four trusted friends and said ‘I don’t want to hear what you like, I want to know what makes no sense, what’s factually wrong, where I might have gone too far’ etc. Then I colour-coded their responses (Family/ Sex/ Dating/ Therapy/ Race/ MISC) and ploughed into the second draft. I’m only meticulous when it comes to writing; nothing else in my life.

It must be brilliant to finally have your book release approaching. How does this feel? What do you want readers to learn, or take from, your novel?

The learnings and responses I’ve had are varied and always buoying. Lots of white people (mainly women, but a few men) have said that they’ve learned something from it – often that touching a black person’s hair isn’t alright – even if “well-intentioned”, while black men have found solace in the the pain of having to be strong and black from it and black women have said that it’s made them feel less alone in their experiences.

Do you think that fiction is an effective way to bring real life issues to people’s attention?

I think it can make some truths that are too painful to bear both accessible and palatable. I think it might also make truths easier to write, when you as the author can give yourself some distance from it. I’m not Queenie, not by any measure, but I see the world through the same lens as her and have had similar experiences, and while I don’t have an exciting enough life to write memoir, it was so easy to construct a story around what I know and have experienced.

When you were younger, what authors did you look up to, or who inspired you to become a writer?

Malorie Blackman was I think the first – Noughts and Crosses blew my mind, and I’ve read everything she’s ever written. Helen Fielding is an obvious inspiration, and so was Sue Townsend. The Adrian Mole series, along with the Georgia Nicholson series by Louise Rennison were so much of my youth.

I like flawed, slightly odd, not necessarily popular protagonists who don’t care about being liked. One of my favourite things I recently read that Louise Rennison said of Georgia Nicholson was: ‘I wanted Georgia to be a decent person. I wanted her to be someone who is a bit stupid and self-obsessed and difficult and funny and rude, and a bit jealous and all those other things. But I wanted her to have a good heart.’ And I think I understood this from her books in my childhood and have always understood that women don’t have to be nice and perfect. I’m certainly not.

Being a writer gives you a certain freedom to write about issues that affect you and society in general. How has your position as a woman of colour has inspired or influenced your writing career?

I can only write through my own lens, so being a black woman has completely shaped my writing. Matters of race resonate with me on a very deep level, because they completely concern me and my life and family. I can’t tap in and out.

There have been a number of successful texts recently talking about racism in the UK. How do you think books, such as Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race and Brit(ish), have made a difference to the perception of racism in the UK?

I think they’ve mainly made people who didn’t already know – both readers and those in the publishing industry – aware that people didn’t just discuss racism in the eighties and solve everything. That in itself is phenomenal.

Do you think that representation and marginalisation of minority groups is more of an issue in the media industry than in other professions?

No. Parliament is completely unrepresentative of the UK, as is the police force. Sport, too; football, for example, is full of black players who don’t make it beyond the pitch and rise to the upper levels of management and punditry like their peers do. Underrepresentation is a huge issue everywhere, in probably every institution.

More generally, what are your future plans for your career? Are you planning on writing any more fiction in the near future?

Book two is happening! I finished a first draft before Christmas 2018 so I could throw it at my editors and be left alone for the break, and I’m gearing myself up to do the edit (which is my favourite part!) now that Queenie is out in the wild. I can’t imagine writing non-fiction, I’m not disciplined enough and don’t think the first few pages would get through a legal read…

For any young women who are budding writers, what advice would you want to pass onto them?

I have a few pieces of advice:

1) Know that your voice is valid and be confident in that.

2) Always people to read your stuff over, and push them to be critical, and learn to take criticism; it’s not personal. Even though writing is solitary, collaboration is vital. Not one person knows everything.

3) Keep it moving; in that you should try not to sweat it over word written because odds are an editor will chop that whole sentence. Just get it OUT in the first instance; everything can be reshaped.

4) Read widely, even while you’re writing.

5) Even if you can’t whip your laptop out and write while you’re commuting or whatever is stopping you from being at a desk, jot notes down in your phone. I’d hate to count the number of times I thought of a plot point and forgot it 10 minutes later. Devastating.

Featured image credit: Lily Richards