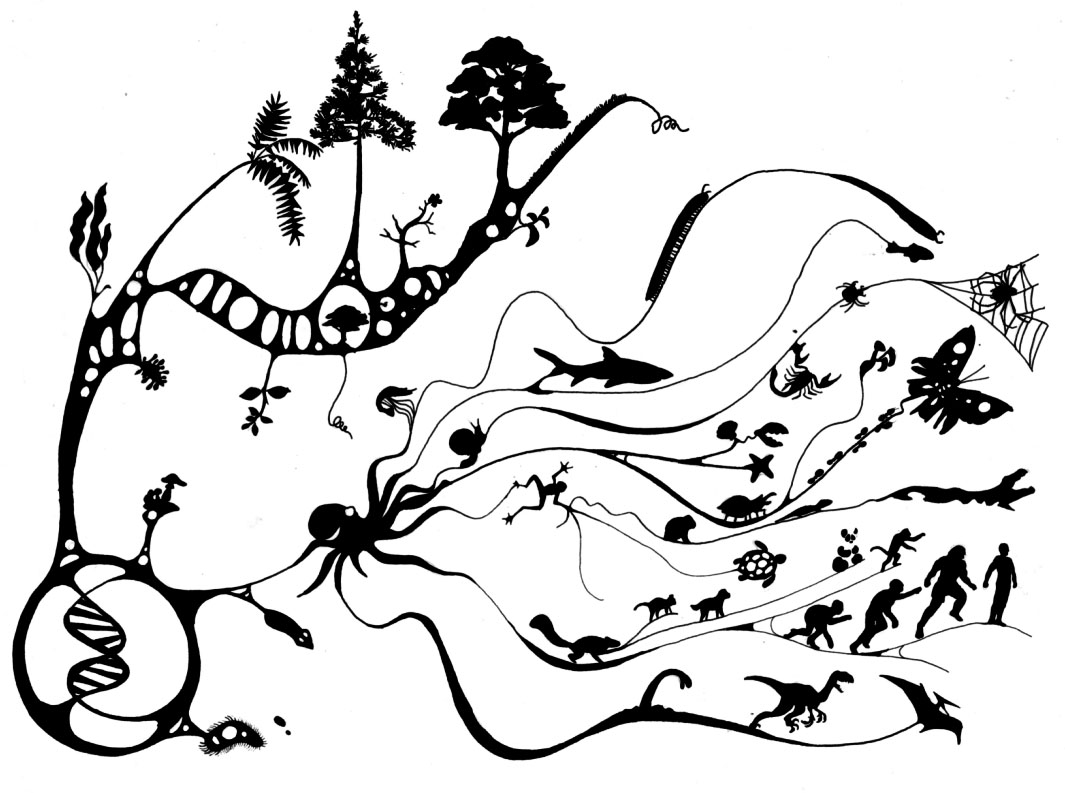

De-extinction; the term given to the notion of bringing vanished species back to life. The concept has been hovering between reality and science fiction for more then two decades since the release of Michael Crichton’s famous novel unleashing the dinosaurs from Jurassic Park on the world.

For most of this time, the reality has lagged greatly behind the fantasy and with many more species on the brink of extinction, a small group of researchers believe that cloning could be the answer and reverse that trend.

So what is the recipe for resurrection? We all learnt about Dolly the Sheep back in secondary school, but in case you have forgotten, Dolly was the first mammal to be cloned from an adult somatic cell, using the process of nuclear transfer back in 1996.

She had three mothers (one provided the egg, another the DNA and a third carried the cloned embryo to term). In this process, an adult cell’s nucleus is transferred into an unfertilised oocyte that has had its nucleus removed. This hybrid cell is then stimulated to divide via electric shock. When it develops into a blastocyst it can be implanted into a surrogate mother.

Since then, cloning has undergone vast amounts of research, eventually leading up to Fernandez-Arias’s clone – the closest anyone has gotten to true de-extinction. This research involved reviving the wild goat, known as a bucardo, a species originating in the Pyrenees- a mountain range that divides France from Spain.

Cells from the last living female bucardo were preserved in labs in Zaragoza and Madrid. Nuclei from these cells were implanted into emptied goat eggs then implanted into surrogate mothers. From the 57 implantations, only 1 survived until birth; which eventually died a mere 10 minutes after birth due to a severe lung defect.

What is next for de-extinction? The next thing to be in the spot light for de-extinction is the red breasted passenger pigeon, hunted to extinction over a century ago, is suggest to have the potential for revival from just a museum specimen.

Geneticist George Church at Harvard University suggested that by transferring key genes into the nearest living relative, the common rock pigeon, this can be achieved.

Firstly, the process requires the assembly of a passenger pigeon genome from DNA fragments in a museum specimen, with that of the rock pigeon, its living street-wise cousin.

This process involved identifying and synthesising mutations that distinguish the passenger pigeon- that give it a red breast, a longer tail, and other key traits. By swapping those bits of DNA for the corresponding bits in rock pigeon stem cells, scientists essentially create passenger pigeon stem cells. These stem cells are then converted into sperm cells – future eggs and sperm – and are then inserted into rock pigeon eggs.

What hatches will be rock pigeons bearing passenger pigeon sperm and eggs. These can then be bred and reintroduced to the wild.

However, this raises the question, just because it looks like a passenger pigeon, is it really a passenger pigeon?

In recent years, humans were the ones who wiped these extinct creatures out, by hunting them, destroying their habitats, or spreading diseases; thus suggesting another reason for bringing them back.

If we drove a species to extinction, we surely have an obligation to try and bring them back. Some other scientists who favour de-extinction suggests that by resurrecting the extinct, it will promote new biological diversity, benefit ecosystems, and the development of drugs that are derived from natural compounds have been found in wild plant species which are vulnerable to extinction.

Thinking back to Jurassic Park, the dinosaurs are resurrected for their entertainment value – to create a theme park. The disastrous consequences that follow have cast a shadow over the notion of de-extinction, at least in popular culture. But people tend to forget that Jurassic Park is pure fantasy.

Concluding to the idea held by some who protest, suggesting that reviving an extinct species amounts to playing god.

In reality, the only species we can hope to revive now are those that died within the past few 10,000 years and left behind remains that contain intact cells or, at the very least, enough ancient DNA to reconstruct genomes.

This leaves us to question: If it can be done, should it be done?