Wes Anderson has carved a niche with his distinct cinematic style, marked by quirky characters navigating charming, dreamlike realms. While his unique style remains recognisable even as it evolves with time, other commonplace aspects of his work refuse to evolve in the slightest and deserve a closer look – namely, the consistent pervasion of Orientalism and Eurocentricity.

In his book Orientalism, Edward Said reveals how Western media often depicts non-Western cultures as exotic and statically unchanging, framing them as the “other” – backward and inferior. This portrayal was historically used to justify Western colonial presence in countries such as India, claiming they would “guide” them to civilisation. However, critical scholars like Patnaik, Roy, Shiva and others unveil how the colonial policies enacted, such as heavy taxation and skewed trade practice, facilitated massive outflows of wealth and resources. This resulted in famine, poverty, and countless deaths. The presentation of non-Western cultures in modern art as backward helps sustain this colonial narrative.

Consider Anderson’s renowned film The Darjeeling Limited. This beautifully crafted story effortlessly entertains with the intricate, tender and comically bizarre dynamics between three brothers as they travel through India. And yet, it was as uncomfortable a watch as it was charming. India is reduced to an exotic backdrop, exemplified by scenes where the brothers “pray” at shrines in a stereotypical style, lacking any genuine religious context. Most disturbing was the scene in which an Indian child dies, simply to trigger an emotionally bonding moment between the brothers and aid their character development. Similarly, in his recent work The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, Anderson refers to “yoga powers” in a lackadaisical fashion without delving into their authentic context, diminishing India’s rich culture to mere aesthetics. In his film Isle of Dogs, set in Japan, Anderson’s central characters are English-speaking dogs. By choosing not to translate the majority of Japanese speech, Anderson effectively marginalises Japanese characters in a film based in their own homeland. The above examples present only a fraction of the ways in which Anderson stereotypes or alienates different cultures, subtly suggesting their inferiority to the West.

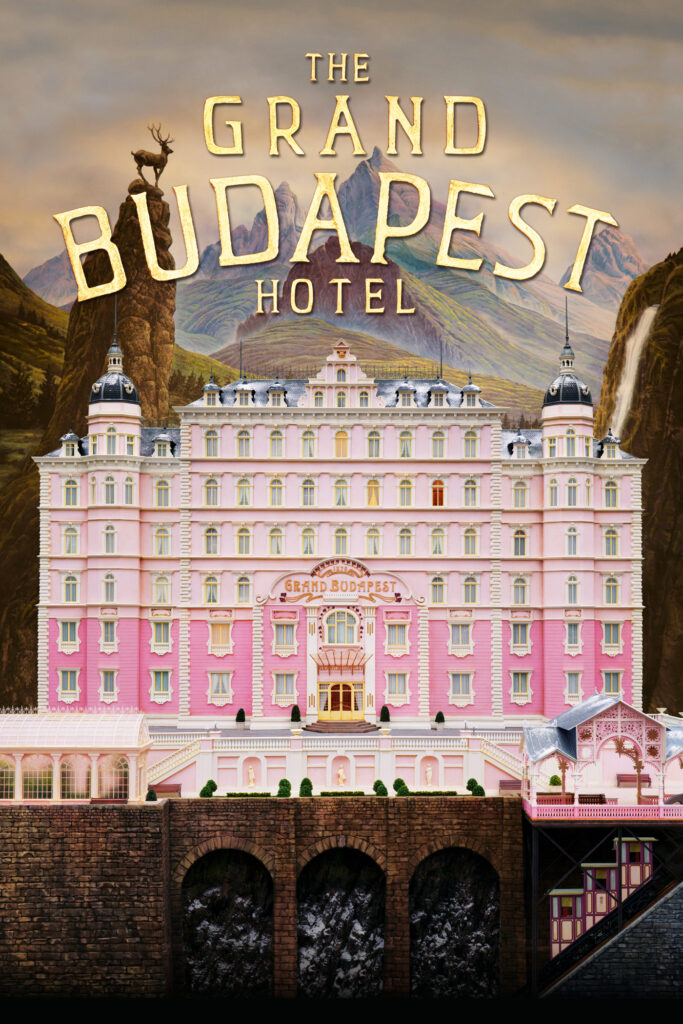

Eurocentricity rears its ugly head in the form of the white saviour trope, which often appears in many of Anderson’s films. Grand Budapest Hotel stars Zero (Tony Revolori), an ‘Eastern’ lobby boy who works for white hotel manager Gustave (Ralph Fiennes); while they share touching moments, there is a consistent representation of Gustave as a ‘civilising’ influence on Zero. This theme of hierarchical dynamics persists across Anderson’s works, as seen between the American Tenenbaum family and Indian servant Pagoda (Kumar Pallana) in The Royal Tenenbaums, or American student Tracy (Greta Gerwig) and her Japanese peers as she leads them in rebellion in Isle of Dogs. In all these films, Western characters assume enlightened or saviour-esque roles, overshadowing their non-Western counterparts.

These portrayals are crucial to recognise, especially considering similarities between the Orientalist discourse used to justify colonial rule and present-day exploitations. For instance, in the development sector; the West’s presentation as “more developed” justifies their interference in the development trajectory of supposedly “less developed” nations, concealing their pursuit of profit behind a veil of benevolence. For example, their push for trade liberalisation in India has allowed corporations like American giant, Monsanto, to profit immensely by selling expensive genetically modified seeds on the Indian market (for more, see Vandana Shiva’s analysis Seeds of Suicide). Crop failures from these “modern” seeds have plunged farmers into debt. The distress caused by such exploitative practices has contributed to alarming rates of farmer suicides in India – in 2022, CNN reported an estimated 30 suicides daily. The implications of Orientalist representations are as significant as ever.

Returning to Anderson, whilst he undeniably possesses talent and flair for filmmaking, his fetishisation of other cultures presents a problem. Collectively, such Orientalist presentations perpetuate a narrative that upholds Western superiority and facilitates ongoing exploitation. Unfortunately, Anderson’s charming style is only skin deep. Orientalist discourse and exploitative power relations are still very much around today, just buried, layered and painted to look pretty. In this regard, Anderson is undeniably a master.