words by Gina Brennan, Staff Writer

The trauma and struggles faced by the working class in the UK are beginning to be more widely acknowledged, perhaps due to the increase in the number of families and individuals facing poverty under the Conservative government. Much of the UK population is starting to unlearn the neoliberal idea of poverty caused by individual fault rather than systemic failure, an idea cemented in the UK’s consciousness by Thatcher in the 1980s, and is beginning to wake up to class mobility being a near impossibility.

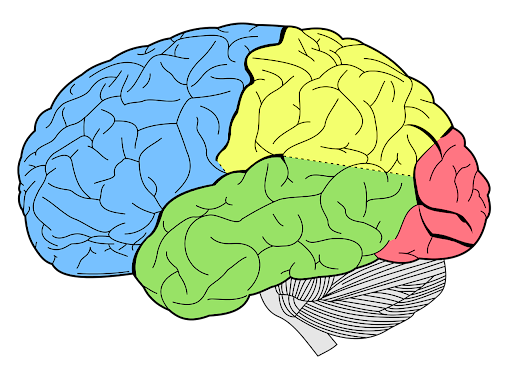

However, in addition to the unavoidable economic struggles, more awareness must be raised around the prevalence of biological struggles that are becoming increasingly apparent in socioeconomically deprived populations, namely the disproportionate number of deprived individuals facing neurological disorders such as ADHD, a neurodevelopmental disorder present from childhood. These neurological disorders are yet another obstacle out of an individual’s control that compounds the economic struggles faced by the working class to increase the inaccessibility of class mobility, as if there weren’t enough obstacles already.

Neurological disorders are a product of both nature and nurture, two aspects of life that are inseparably intertwined. A person’s DNA, their “nature”, undoubtedly can create risk factors for neurological disorders unaffected by the environment (“nurture”) a person is exposed to. However, neurological risk factors can also be caused by a person’s environment, especially in childhood, which is why it is paramount to neurological health that a person is raised in the best possible circumstances. Here is where the problems begins to take shape; those raised in socioeconomic deprivation are at an immediate disadvantage, and so are at far greater risk of developing disorders such as ADHD through no fault of their own. An investigation into the link between socioeconomic deprivation and ADHD by Hire et al. took place in 2015, discovering that there is a significant correlation between the quantity of ADHD diagnoses and the deprivation index of regions in the UK; in other words, more deprived areas had higher numbers of people with ADHD. The least deprived areas had the lowest numbers of ADHD cases, and the most deprived had the highest numbers. These results have been replicated, for example with Russell et al. presenting similar findings in 2014, proving their reliability. Perhaps even more worrying is that there were large discrepancies in ADHD cases in regions geographically close together, showing that other environmental aspects (eg. schools) are unable to significantly counteract the impact of deprivation. The link between ADHD cases and the environment of socioeconomic deprivation is clear.

In addition to the presentation of results showing the association between ADHD and socioeconomic deprivation, there are deeper scientific grounds for concern. Epigenetics is a relatively new field, describing the interaction between genetics and environment. It explains that your environment can physically alter your DNA by adding epigenetic tags – in basic terms, these tags can switch genes on or off. In this way, the environment alters your genetic material by changing which of your genes are expressed. These changes appear to be able to be passed on to your children, especially in the context of ADHD (although it is unclear as of yet how this happens). Links between epigenetic tags, socioeconomic deprivation, and ADHD have been established, as well as the passing on of these tags to children. This is incredibly insidious; not only does your environment as a child affect your chances of developing neurological disorders, now the environments of your ancestors can too. In this way the struggles of poverty are passed on down generations, increasing your risk of developing disorders if your family is, or was, poor.

These neurological disorders not only increase the struggles that the working class face, but also create struggles that are inherited down generations. This is deeply insidious. Neurodevelopmental disorders like ADHD have very disruptive symptoms from childhood, disturbing people’s efforts in school and work environments. The increased risk of deprived people developing them creates yet another obstacle to them working to the standard of their privileged peers, and so constitutes another barrier to class mobility. The development of neurological disorders due to poverty helps to keep those people in poverty, and the way the epigenetics of neurological disorders can be passed on through generations compounds this. This again emphasises that poverty is not the fault of an individual.

Additionally, the failure of the government to even acknowledge this research, let alone act on it, can be seen as another way they are keeping the working class poor. These findings call for a restructure of support for neurological disorders across regions to provide help where it is most needed and lessen the impact of socioeconomic situations on neurological conditions. Action must be taken to exonerate children from being permanently affected by the circumstances and location of their birth. The government, in failing to implement this, proves their indifference to the struggles the working class face and their reluctance to help people facing socioeconomic deprivation. Not only do people living in deprived circumstances have to work so much harder than their more privileged peers due to the economic difficulties and time constraints caused by poverty, but they must also work through their increased risk of developing neurological disorders that, by definition, make it harder for them to accomplish this work. These discoveries represent perfectly the struggles faced by the working class in the UK, illustrate exactly how inaccessible mobility between classes is, and demonstrate how out of touch the upper class and the government are when suggesting the poor must simply work their way out of poverty. How can they work their way out of their DNA edited by the deprivation themselves and their ancestors faced?

With the establishment of associations between deprivation and neurological disorders such as ADHD, there is a pressing need to counteract this through support for both disorders and socioeconomically deprived people. Something must be done soon to lessen both levels of deprivation and its impact on neurological conditions. Without this, an unnecessary and high prevalence of ADHD will shortly, if not already, become pronounced, caused by the high levels of deprivation in the UK and around the world. This will have a huge impact on both society and the individuals. Support must be implemented to counteract this, starting now.