Words by Oliver Mizzi

When we think about Afghanistan we think of America’s long war – the forever war. We don’t think about the early days of the Afghan tragedy. We don’t think about the Soviet Union’s Vietnam. This is what Svetlana Alexievich’s book Boys in Zinc covers.

A work of documentary literature, the book weaves the testimonies of those affected by the war, to reveal the disturbing reality of an endeavour that rotted Soviet society. Importantly, it bypasses the narrative of the Soviet leadership that spoke of “our international duty, about defending our southern borders”; a Soviet leadership that sent their youth to die performing their “internationalist duty”. I don’t think any of the interviewees believe that after going through the war. When asked by a boy if the Union should be in Afghanistan, a nurse recounts “I was indignant. ‘If we weren’t there, the Americans would be’… As if I could prove that somehow”.

Often at times the reality of the war is hard to reconcile. A Major says: “They’ve already written about the war as ‘a political error’ and called it ‘Brezhnev’s reckless gamble’”. How can a soldier come to terms with fighting for a “political error”? A Senior Lieutenant can’t: “I don’t want to hear about a ‘political error’! I don’t want to know! If it was a mistake then give me back my legs…”.

There is terror in the testimony. It’s like a living nightmare, and it reaches out to you from the pages. It’s the nightmare of the soldiers, mothers, wives, medical staff and civilian employees who are now damaged physically or psychologically, or both. At whose hands? A private whose wife left him blames “the mummies in the Kremlin… Those cursed mummies!”. A mother weeps at the military commissar who refused to stop her son going to Afghanistan: “you’re soaked in my son’s blood! You’re soaked in my son’s blood!”. Nobody blames the Afghans, the “spirits”.

Whilst the zinc coffins fly back from Afghanistan to distraught mothers, Soviet society is “living and acting as if we didn’t exist out there. As if there wasn’t any war” recounts a military advisor. All the while Afghan Sheepskin coats and Japanese cassette players are entering the Soviet Union along with ‘Load 200’, the zinc coffins. “There is a joke going around that people in the Union only learned about the war in the commission sales shops”. This the picture of late Soviet society, as painted by the accounts in the book.

The book doesn’t just focus on depicting the rot of Soviet society. Naturally, a book based on the testimonies of a war is going to dive into the subject, and in doing so the book does justice to those lived experiences. They say war is hell, but not necessarily because of the enemy. “If the Afghan ‘spirits’ don’t kill you, your own side will”. You soon realise that the Soviet soldier has “boiled buckwheat for breakfast, lunch and supper”, and it comes as no surprise that to help survive the insanity of war, there’s vodka from the Union and hashish from Afghanistan.

But it’s not just the time in the military base that is recalled, soldiers have to venture out into combat too. “In a battle you go numb, stop feeling. Cold reasons and calculation. My automatic is my life”. To survive unscathed is one thing, but over 50,000 Soviet soldiers were physically wounded: “Someone said: ‘The major’s lost his legs, I feel so sorry for him.’ The moment I hear him… I got this pain right through all my body… It was so terrible that I started howling”.

The medical staff who treated the wounded and civilian employees fared no better, everyone stands face to face with death. “They brought in a wounded man… He opened his eyes and looked at me. ‘That’s it then,’ he said. And he died”. Many assumed civilian employees to be “prostitutes or check grubbers” to get more out of the war. But they’re damaged too. One recounts how she isn’t the person she used to be: “And I cry all the time. I cry for that bookish little Moscow girl”.

Boys in Zinc doesn’t shy away from the war, nor the pain left in its aftermath. It speaks truth to power, and this is evident in the trials Alexievich was embroiled in after the book’s initial publication during the instability that embroiled the former Soviet Union. As much as it was a shock for post-Soviet society then, it’s still a shock to read those same accounts today. Many of those who’ve read it know of its importance. There’s a song about the war titled ‘Hello Sister (Don’t Tell Mum I’m in Afghan)’. If you want to understand the title and the truth behind the song, then read Boys in Zinc.

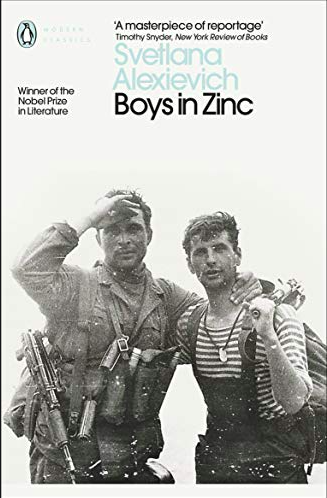

Image from Penguin Books.