As I sat at home on my sofa mid-lockdown, having just finished the last page of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, I couldn’t quite believe what I had read. I was overwhelmed and shocked. Shock turned into frustration, and then anger. “How is this woman not taught at every level in science?”, I wondered to myself. “How is she not considered to be one of the most important women in science as we know it?”. Her name, perhaps, had been lost in the cacophonous tides of history; she completed her work in the 1950s, a decade which bore witness to the post-war baby boom, the start of the Cold War, and the burgeoning of the civil rights movement in the United States, to name just a few of the world-historical events that occurred at mid-century.

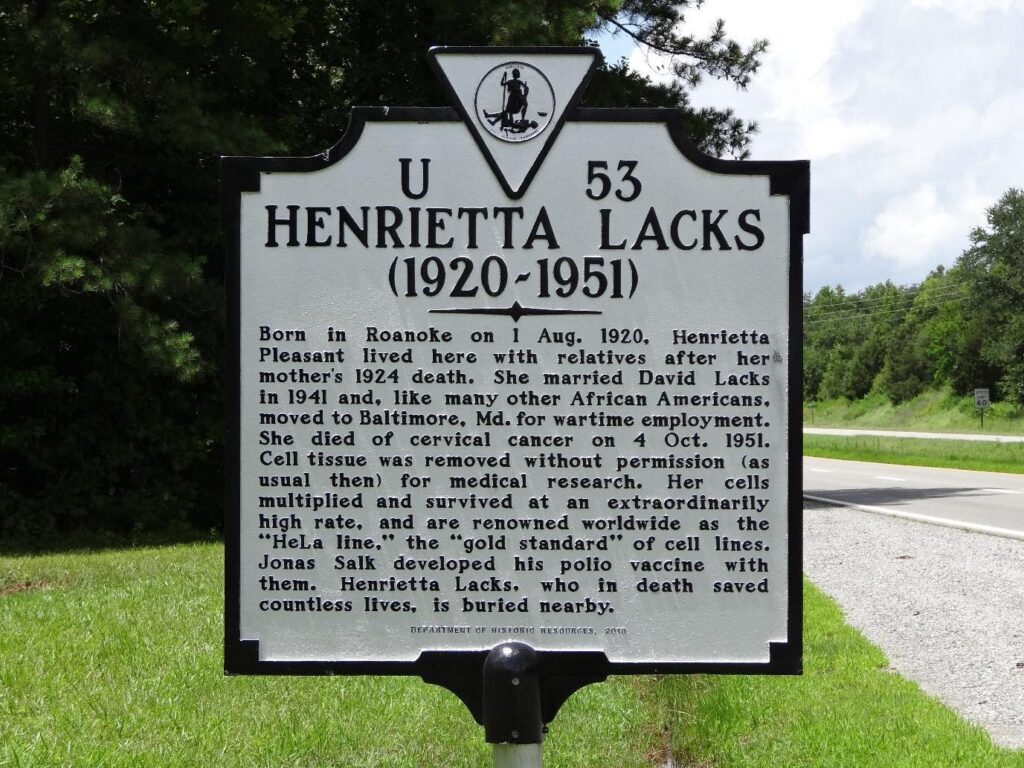

Henrietta Lacks was an African American woman born in 1920, in Roanoke, Virginia. She was a tobacco farmer, raised by her grandfather after her mother’s death in childbirth. Her grandfather also happened to be looking after another grandchild, Henrietta’s cousin David, who was also known as Day. And, on 10th April 1941, they were married. Soon, the economic effects of World War II on the American labour market sent the family northwards to Maryland, to take jobs at Bethlehem’s Steel Sparrows Point steel mill. Better pay brought with it the potential for a better life. They lived in Turner Station, a largely African American community outside of Baltimore where many of the steelworkers lived.

Soon after having her fifth child, Henrietta complained of a “knot” inside her to friends and family. Irregular bleeding and the feeling of a lump on her cervix sent her to the Gynecology department at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins Hospital. Sure enough, in February 1951, the presence of a hitherto undetected cervical tumour was confirmed by a biopsy. Henrietta hid the diagnosis from her family and only told Day, her husband. The first round of treatment, a standard series of radium treatments, involved stitching small glass tubes of radioactive metal secured in pouched, brack plaques to the cervix. On one of these procedures, the surgeon extracted two small tissue samples; one from Henrietta’s tumour, and a healthy sample. In fact, Henrietta’s samples were one of many such samples extracted by the physician George Gey, who was the head of tissue culture research at the time. He was trying to find an ‘immortal’ cell line for use in cancer research. He had been unsuccessful until his encounter with Henrietta’s cancerous cells. They multiplied at an exponential rate – filling up any test tube used. The cells were named HeLa, after Henrietta. Henrietta was unaware of this research; it was not uncommon for patients to have their tissues studied without their consent.

Sadly, by September 1951, the cancer had spread throughout her body and, by October, Henrietta had died. The HeLa cells continued to survive and thrive long after Henrietta’s death. Henrietta’s case has since become a fundamental study in the field, contributing material to countless research breakthroughs and accomplishments. She became known as the mother of virology, biotechnology and tissue culture. Her cells were used to initiate research on standard lab practises for freezing and culturing cells, and for how viruses act and reprogram cells. They were used to develop in vitro fertilization, isolation of stem cells, as well as research into AIDS, cancer, and the effects of radiation. Her cells have been infected with an array of diseases, from salmonella to tuberculosis. She even helped us to understand that a normal human cell has 46 chromosomes, making genetic disorders exponentially easier to diagnose. The possibilities appear to be endless; over 60,000 articles have been published on research done on HeLa.

Despite her inestimable scientific importance, until the 1970s Henrietta’s role was unknown even to her family. Her situation became one of many examples of the lack of informed consent in the twentieth century which catalysed the debate surrounding patients’ informed consent for the use of their cells in research. And, in 2013, the National Institute of Health granted the Lacks family control over how the data on the HeLa cell genome could be used. The NIH’s HeLa Genome Data Access working group was developed, which reviews and researches applications for access to the HeLa sequence information. The Lacks family finally had access to information, but was it too late? For years, Henrietta’s family had received no financial benefit from all of this and continued to live with limited access to healthcare.

In 1991, the common rule was introduced, requiring all doctors and scientists to inform people when they are participating in research. They must sign consent forms informing them of what the research is, how long it’s expected to last, what the risks are, and compensation information. Privacy, consent, and anonymity are now serious considerations; things that Henrietta and her family were not afforded.

As time goes by, we continue to learn about the importance of HeLa cells and the amazing woman behind them. Reading The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks changed my life, and I believe it would change the life of anyone who reads it. It was one of the first stories to focus on the legacy of Henrietta herself. In other words, the book enables people to understand the truth behind the research.

For every inspired scientist or doctor, her name and story need to be heard and discussed to understand the gravity of their actions inside and outside the lab. What would Henrietta have thought of Gey sending her cells to other labs? What would she have thought knowing her cells were used to create billions of pounds worth of profit, whilst her family were left unable to pay for health care and education? It’s clear this story has a role to play in our education system. The sad reality is that we still aren’t taught about this incredible story, and this needs to change.