Words and photos by Luisa De la Concha Montes

Photoworks annual festival launched on the 24th of September and will be ending this Sunday. Due to COVID-19 limitations, the festival had to take a different approach to previous years. However, their response to the restrictions imposed actually served as a creative opportunity to explore photography in its many forms. Through the use of digital and physical spaces, the festival allowed viewers to actively reflect and question the role that photography plays in our current context.

Photo-Walk

Photowork’s physical exhibition consisted of billboards spread around the walls of Brighton. This made the visual experience completely different to a traditional exhibition; to an extent, it felt like a scavenger hunt. I found myself alternating between my screen and the real world, using the Photoworks map to look for the location of each piece. However, I also found myself searching for correlations between the photos exhibited and the place where I found them.

Gloucester Road

For instance, Guanyu Xu’s Temporarily Censored Home was placed next to an art gallery which had a window display of small framed prints. The duality of Xu’s photograph, which depicts many photos within the photo, next to the framed prints worked incredibly well. Through subdued visual nudges, the exhibition felt naturally attached to the urban façade. In a way, it suggested that the artwork does not stop as soon as our gaze moves away from the frame.

Vine Street

This photograph, titled Business as Usual by Alberta Whittle was placed next to Junk, a distinct vintage and second-hand shop. It doesn’t really matter if the decision to place them next to each other was deliberate or not –it works. Junk’s eclectic mess is almost like the real-life version of Whittle’s collage. In both instances, our gazes feel confused and overwhelmed by the number of items in front of us. When entering Junk, we experience a need to look at everything at once; however, this is met with the practical impossibility of only being afforded a single pair of eyes.

Whittle’s Business as Usual proposes a visual solution to approach our oversaturated capitalist environment. By merging incongruent items together, and by creating a narrative through them, Whittle leads the viewer into a fictional universe that transforms intimidation into humour. Elements whose connotations often disturb us (coins and money) are re-contextualised alongside harmless objects (coconuts, plants, bananas), making the final product a satirical reflection on the absurdity of our own habits and preoccupations.

North Road

There are two main things that fascinate me about Ronan Mckenzie’s Explorations of Brown; the first one is the context in which it was placed, and the second is the angle of the subjects. The colour of the carpet is almost the same tone as the walls in North Road, making the image feel completely natural within this urban landscape. Moreover, since both subjects are looking upwards, and since the image is placed higher up, it almost feels as if I was looking through a window. This play of gazes –me looking at them and them looking at me in return– is arresting, and intimate. It makes me think that even if I wasn’t actively looking for this image, it would have made me stop.

Interactivity was one of the festival’s greatest accomplishments. The whole premise of the exhibition is that photographs are not static; they are works that can transform the viewer but that can also be transformed by the viewer. The hierarchy that is taken for granted in traditional gallery environments was uprooted; the viewer can create their own route, and what is even more, the viewers themselves can be completely passive. In fact, I would be interested in knowing how these photos changed the experience of the city for those that weren’t actively looking for them. How did the passers-by that were just on their way somewhere else react to them? And what did the people that weren’t aware of the festival make of them?

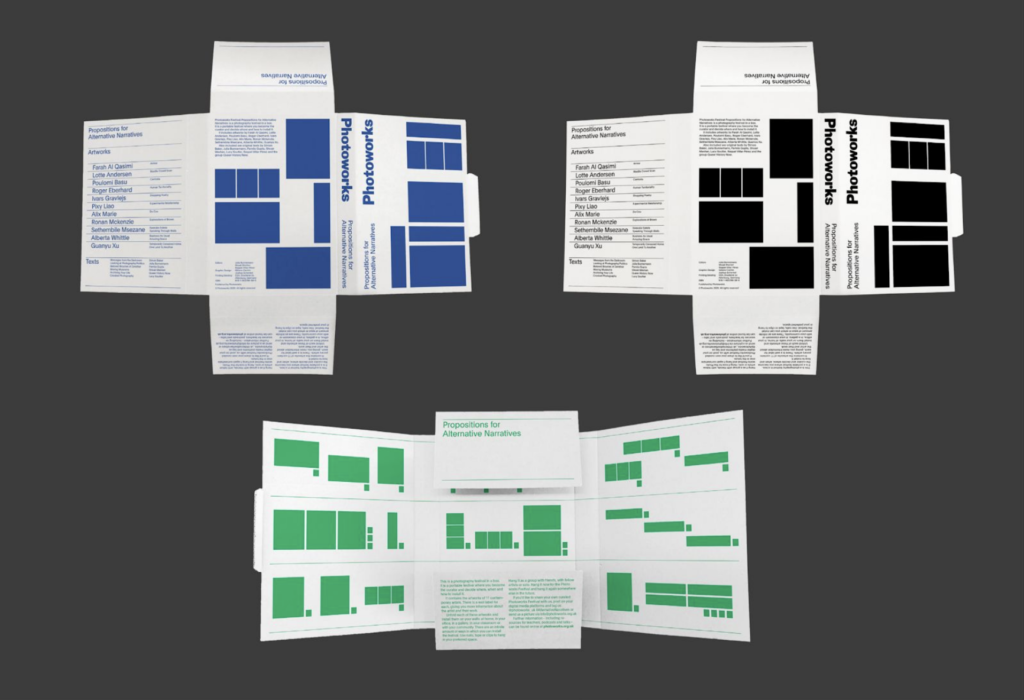

‘Festival in a Box’

In addition to my Photo-Walk, I received a copy of Photowork’s ‘Festival in a Box’, which included prints of all the artists’ work. The concept was quite simple, yet innovative: “a portable festival where you become the curator and decide where and how to install it.” Rather than reviewing each individual print, I’d like to talk about the process of installing the photos in my home, as I believe that this can give further insight into the way in which the format helped me reframe the relevance of the work.

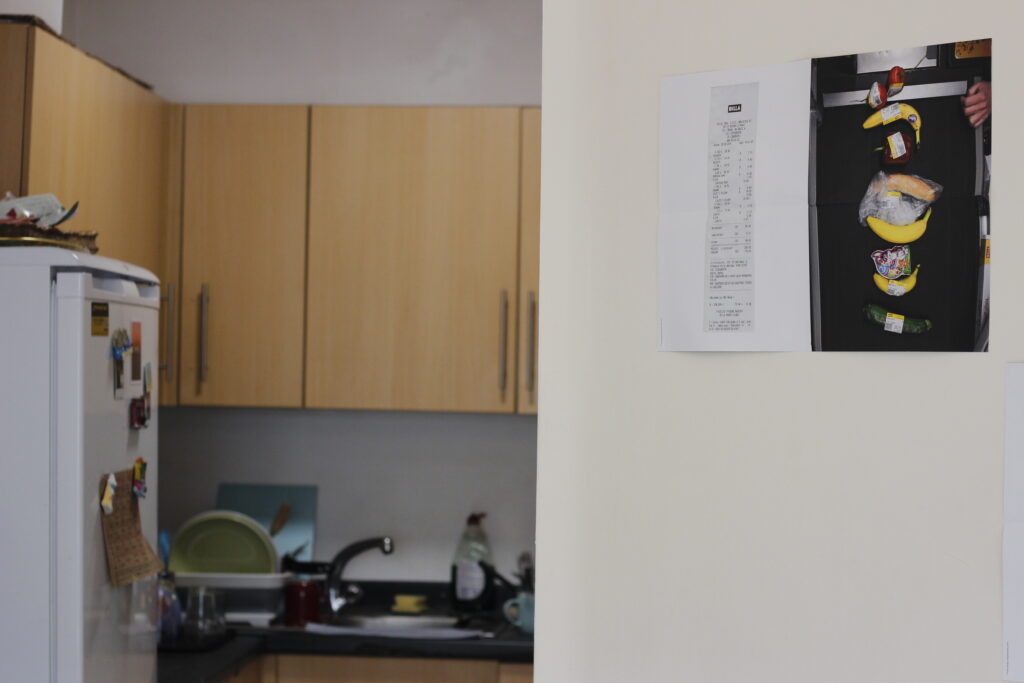

I did not open the box on my own. I told one of my housemates to open it with me. Her immediate reaction was of excitement; we live in a student house, meaning that our walls are quite bare. The idea of being able to completely reinvent our home with prints was truly exciting. When looking at Ivars Gravlej’s Shopping Poetry, my housemate immediately said, “this one should go in the kitchen”. I couldn’t disagree.

Kitchen

The freedom of being able to contextualise images in an informal way was extremely refreshing; there wasn’t much thinking behind our decision to place Gravlejs’ images in the kitchen. We just felt as if they belonged there, alongside our own groceries and our own shopping receipts. By actively breaking down the traditional separation between the public world and the private world, the work itself was transformed into something more powerful and personal. These photographs are no longer just prints that some artist made, they are prints that I will see every morning while I have my breakfast.

Landing

When I was deciding where to place Farah Al Qasimi’s work, which is about domestic traditions in the United Arab Emirates, I noticed that one of her photographs depicts a drying rack. Without hesitation, I placed that image in our landing, right above where we normally put our drying rack. Again, these decisions were not based on some inaccessible art knowledge, they were natural reactions to my immediate surroundings.

In fact, writing this review was not a linear process; I constantly stood up, walking around the house placing pictures and conversing with my housemates about where they should go. We’ve become accustomed to the habit of looking at pictures passively that this whole experience felt strange. My subjectivity almost made me feel guilty. I was not sat on my chair, scrolling aimlessly down a screen. I wasn’t wandering through a gallery, taking notes and reference pictures either. Instead, I was an active subject in the process, deciding which images meant the most to me, and where I would like to see them. As Ariella Azoulay proposes, instead of just looking at the photos, I was “watching” how they could potentially transform our home.

The festival was overlapping in many senses; it consisted of actual prints, photos in the streets, Instagram take-overs, Zoom conversations and online essays. This assured that it reached different publics in different ways. Some, like me, actually took a Saturday off to go and see them in the streets, but others might have only attended the online events or unknowingly seen the photos as they walked past them. This well-planned interactivity and accessibility managed to ensure that it reached many people, and more importantly, it was a testament to the fact that photography lives outside photography itself. It’s not a ‘single’ event; it’s multifarious. Photography can be a conversation, but it can also be what you encounter on your walk to the shops, or an Instagram story. The biggest achievement of the Photoworks 2020 Festival was exactly that; it debunked the hierarchical structure of the art world, demonstrating that photograph is ultimately kept alive by its viewers.

Finally, the festival can also be read as a metaphor for the buzzwords that keep on defining our COVID-19 experiences: transformation, change and instability. The form of the festival, akin to the form of our lives right now is not clear cut; it can often feel confusing and overwhelming. However, in the context of photography, words like ‘transformation’ and ‘instability’ can become a utopian escape. Throughout the week in which I was working on this review, I almost forgot that the walls to which I have now attached these photographs are walls that might see me confined and isolated in the near future. In that sense, the fictional narratives behind each photograph worked as a survivalist response to the unpredictability of the world out there, demonstrating that photography can often help us deal with our overwhelming realities.

Click here for more information about the Photoworks Festival.