Words by Eric Barrell

Content Note: violence, sexual assault

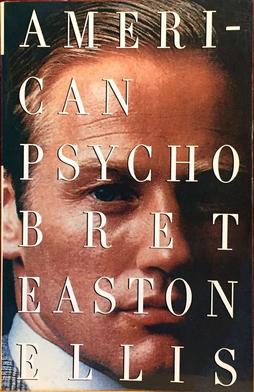

The story of American Psycho is on the surface a simple one: Patrick Bateman – a wealthy Wall Street investment banker in the late 1980s – is obsessed with a hyper-materialistic, artificial idea of perfection. He and his Manhattan elite friends spend vast amounts of time and money on designer clothes, fine dining and perfecting their physical appearance. Yet small moments, such as when a co-worker’s business card has a slightly better font or the booth reserved in a fancy restaurant is not to Patrick’s tastes, result in aggressive outbursts. Patrick’s hyper-maintained appearance is an extension of his unhinged psychopathy within. The egotistic men and simpering women in Bateman’s world are absurdly oblivious to his derangement, laughing off his barefaced admissions that he is a murderous psychopath. As the novel progresses, the reader is taken on a wild ride through Patrick’s increasing descent into insanity in his need to quench his bloodlust.

The most controversial parts of American Psycho – leading to the book often being banned or restricted to over-18’s in several countries – are the extremely graphic descriptions of Patrick’s torture and murder of several people throughout the story. When it was first published, many feminist critics including Gloria Steinem opposed the novel’s explicit depictions of violence against women. Many of these criticisms were abated by American Psycho’s 2000 film adaptation, directed by Mary Harron and starring Christian Bale (who ironically is Steinem’s stepson). The film also had a female scriptwriter, Guinevere Turner, who has a small role in the film as Elizabeth, one of the many upper-class Manhattanite women in Bateman’s life. In both the book and the film, Patrick takes Elizabeth to his apartment to engage in a drug-induced threesome before murdering her to fulfil a grotesque sexual fantasy. While seducing her and the other girl, a prostitute he names Christie, Patrick lectures about the talents of Whitney Houston, listing most of her 1980s discography and which songs he enjoys best. In the book, this is portrayed as one of many inner monologues about Patrick’s music tastes; his obsessions with particular artists such as Whitney and Phil Collins providing a humorous insight into his psyche, whilst also depicting his meticulous appreciation for popular consumer products. In the film, however, his delivery of this monologue to the drug-addled Elizabeth prompts a mocking response. ‘You own a Whitney Houston CD? More than one!?’ she cackles to a stony-faced Patrick.

This scene captures the more overtly satirical perspective Harron and Turner took with the film. Elizabeth finds the fact that the hyper-masculine Patrick Bateman owns Whitney Houston CDs hilarious, and the fact that she is played by the film’scriptwriterer further solidifies Harron and Turner’s mocking of this character. Whilst the book is also satirical and meant to criticise the extremes of American capitalism, Ellis would go on to admit that the character of Patrick Bateman was based on aspects of himself in the 1980s, when, by his admission, he was ‘slipping into a consumerist kind of void’. Book Patrick Bateman feels more unhinged, more of a manifestation of the cruellest parts of the human psyche than the easier-to-laugh-at Patrick Bateman of the film. The reception of both works from their release to now sparks a debate about artistic intent versus reception, and what rightfully justifies artistic censorship.

American Psycho is a dark comedy, and the film expresses this in a more overt way which leaves most audiences laughing at the fragility of Patrick Bateman’s materialism and hypermasculinity. Reading from a perspective of revulsion at his actions and humour at the subtle ways his perfectionist ideals are critiqued, I never felt that the character was explicitly portrayed as someone to be admired. However, something I did take note of was how many of the story’s themes echo many aspects of the 2020 zeitgeist. Patrick Bateman idolises Donald Trump, mentioning him and his then-wife Ivana frequently throughout the book. Many of his victims are from marginalised groups – two of which, a homeless man and a gay man – have pet dogs which he also maims or kills. All the women he encounters are objectified to varying degrees, the ones he murders being a part of his violent sexual fantasies.

It is interesting, then, that many men in current times idolise Bateman. His extreme grooming and fitness regimen would be considered absurd and effeminate in the 1990s. Yet in the social media-driven age of the 2010s, successful marketing and an increased focus on appearance has made male grooming be seen as more masculine and aspirational. Fans of Bateman point out that they admire his ‘alpha male’ personality and aesthetic dedication, whilst rejecting his…bloodthirstiness. In certain internet communities connected to the neo masculinity movements of the alt-right, Bateman is idolised among other outsider male characters such as the Joker for his aspirational masculinity and misogynistic attitude. Reactionary men’s movements are part of the conversation surrounding a supposed ‘crisis of masculinity’ in the 21st century; a backlash against the progress to undo limiting gender roles in the feminist and LGBTQ rights movements. Satire or not, characters like Patrick Bateman are tied up in ideas around idealised masculinity. The millennia-old archetypes that men must be dominant, competitive and strong inform both the products marketed at men and the political standpoints in the current reactionary men’s movement. Thus, revisiting American Psycho and examining exactly what message it seeks to convey is crucial to ensure the story is not diluted of meaning to justify a more malevolent purpose.