By Charlotte Brill

Seeking asylum is an internationally recognised legal right according to the 1951 Refugee Convention, allowing displaced people to apply for refugee status in countries which have signed it. This UN convention recognises a refugee as a “someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted’’ (Article 1A). This looks amiable and protective on paper, but it certainly does not guarantee everyone an equal right to asylum. Whether a devious migrant smuggler or a vulnerable displaced child, almost all asylum-seekers travelling through Europe are generally lumped together as illegal, when they don’t deserve to be.

There is no fully legal way to travel to the UK to claim asylum, but as they are only able to present their claim on British soil, they are forced to go through irregular channels. These desperate asylum-seekers, many of whom were violently displaced from their home and have suffered a myriad of perils on their exhausting journey, face borders upon borders preventing them from ever reaching safety and security in Britain.

Calais, being almost the pit-stop to the UK, is one of the most rigid borders fortifying the British territory. Britain’s combination of physical isolation as an island, and the presence of juxtaposed border controls, mean that checks are carried out before leaving France, rather than after arriving in the UK. According to the Le Tourquet agreement, this makes Britain’s border almost impermeable, at least for asylum seekers deemed ‘unworthy’ of free movement.

In fact, according to the Refugee Council, the UK is only home to approximately 1% of the 25.9 million forcibly displaced refugees across the world. So why, if the UK proudly claims inclusivity and multiculturalism, does such racial discrimination and injustices at our border happen so heinously? Are we really that obtuse?

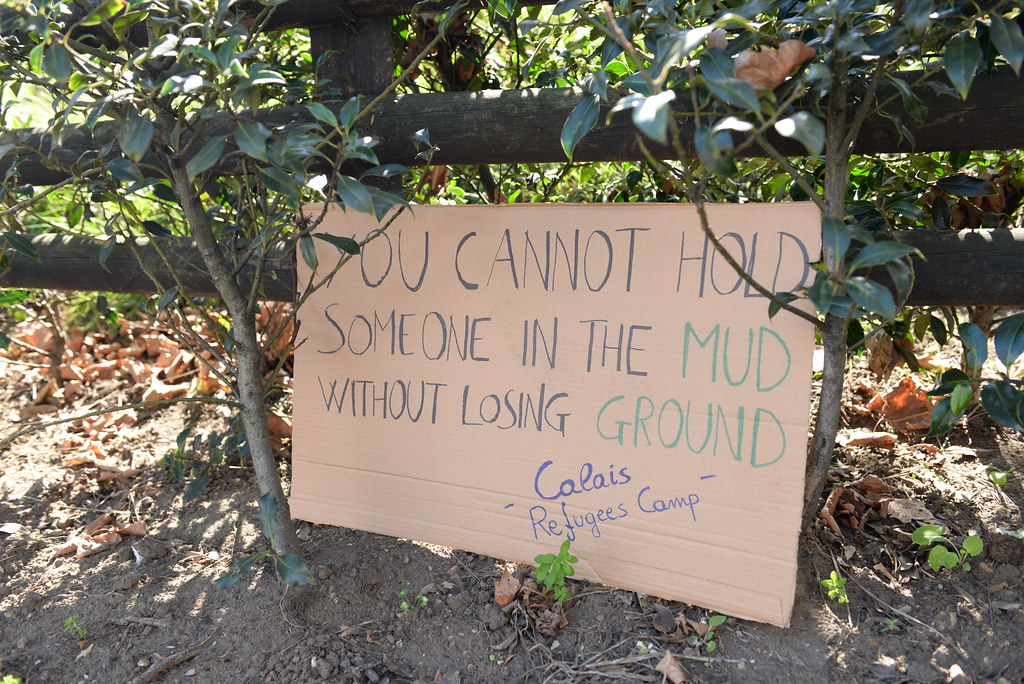

The border at Calais’ role in the European Refugee Crisis has been significant, though rarely positive with it being a locus of state cruelty and brutal practices of segregation. This is epitomised by the harrowing demolition of The Jungle camp in 2014, where around 6000 migrants made makeshift homes. Despite the border’s heavy securitisation, thousands of refugees continue to be drawn to the region. Many migrants simply seek to escape persecution and danger at home, among reuniting with their families, too. Britain is a position of safety cited for having a good human rights record, as well as desirable social support networks.

Yet, as Britain finally leaves the EU, the right of reunification for refugee children remains ambiguous. Currently, the government promises to protect the rights of refugee children in a subsequent immigration bill, avoiding negotiating it into the official EU (Withdrawal Agreement) Bill, but this is yet to be seen. Limiting legal means for children to be reunified with family in the UK will mean an increase in child refugees who will have little choice but to turn to illegal and dangerous means of travel. It makes me wonder whether the image of drowned three-year-old Alan Kurdi, which shook the world and inspired increased international humanitarianism, lost its resonance as time progressed and new images fill the mediascape.

Britain’s immigration rigidity means that the inflow of migrants considerably exceeds the outflow, contributing greatly to the continually problematic and unlivable situation at the Calais border. Trapped in Calais and forced to reside in makeshift camps, on the streets or in the forests, the administration and deportation of copious amounts of asylum-seekers become predominantly the responsibility of the French state, leaving Britain comparatively unscathed. Aware of this unequal division of labour in the Calais borderland’s co-management, President Emmanuel Macron exerted that France could not continue being Britain’s ‘’coast guard’’ by doing its ‘’dirty work’’.

Not only does it put infrastructural strain on French authoritative bodies it also causes immense emotional and moral stress for many individuals working at the border. Britain responded, in the all too common way with political dispute, over a monetary sum of £44.5 million in compensation according to the 2018 Sandhurst Agreement; a considerable amount of money fed directly into the discriminatory segregation and callous treatment of refugees at this heavily policed border. I can’t help but imagine the difference this money (or at least some of) could have for refugees, particularly the vulnerable children, if it was put towards providing legal routes to reunification.

People say we are powerless, but we wield more power than we realise

Instead it is used to protect xenophobic sentiment, echoed by the pervasiveness of Brexiteer rhetoric, disguised as an endeavour to preserve the fallacy of national integrity. Populism is undoubtedly on the rise with the securitisation of national borders intensifying, insofar, that racialised violence and discriminatory injustices are naturalised as everyday occurrences.

The issue is that, although European refugee flow is portrayed and widely accepted as a humanitarian emergency, it is also perceived as a crisis of sovereignty which is only exacerbated by our current turbulent political climate. Asylum-seekers are perceived as a threat to the national imaginary which depicts a bounded territory and a common identity, glued together by shared cultural symbols. By irregularly breaching the fortified border they undermine the state’s power in terms of security and boundedness of the nation-state, revealing uncertainty and vulnerability.

The British government particularly wants to conceal such qualities during this historically sensitive and volatile time. Asylum-seekers, refugees, or often simply ‘others’, who do not fit comfortably into this inflexible understanding of a ‘harmonious’ nation are criminalised. Considering all the heart-wrenching images of squalor, malnutrition and capsized boats, it seems a bit ridiculous that these people are automatically and unquestionably considered illegal threats. Can we really blame them, after all the horrors they have faced, for ‘illegally’ travelling to Britain in search of sanctuary?

Intolerance and criminalisation of asylum is not only rooted in British immigration policy, but it is also integral to everyday public discourse. The negative representation of refugees is routinely internalised, legitimising the repressive securitisation of national borders. How often have you heard a version of the phrase ‘they are stealing our jobs’? I suspect a few times at least, even if not from someone you know personally.

Such phrases are used so banally nowadays that many don’t think twice when they hear them or even use them comically. Xenophobic sentiments at the foundations of these phrases are rooted in an insecurity of the loss of identity, both individually and of a collective national identity which unites these insecure people.

There is so much pressure put on the territorialisation of identity and belonging, whereby place equals identity, consistently leading to mass alienation and discrimination of ‘others’, as seen by the treatment of refugees at the Calais border. When it comes to consumerism, we grab at the chance to be global citizens to maximise our profitability and the availability of resources, but when identity is brought into the mix the anxious individual reverts to the traditional notion of bounded and territorial belonging.

These nationalistic insecurities exacerbate refugees’ challenging and unjust experiences by how they become normalised as part of the everyday practices of segregation, both at the border and within the nation-state. Daily acts of racialised discrimination and violence, including profiling, harassment and disregard, are normalised manifestations of the deep-rooted xenophobia which many people do not even realise is present in our everyday lives.

Largely falling out of the media, the European Refugee Crisis is still a great humanitarian emergency with millions of people being forcibly displaced due to political conflict and war tearing their homes apart. As the UK leaves the EU, it leaves the child refugee reunification policy up in the air. Also, as warfare continues fervently, increasing the amount of desperate asylum seekers, the future seems bleakly troublesome.

There is little that the average individual can do about dissonant politics or for the suffering refugee in France. We can, however, be more open-minded and aware of our beliefs towards refugees, and of those around us. People say they are powerless, but we wield more power than we realise. We have the power to change the rhetoric which will be passed down to the next generation. By being aware of your own beliefs, and of those around you, by questioning and adapting them, we can hopefully increase acceptance, inclusivity, and multiculturalism in the long run.

Image credit: Michael Belka & Ilias Bartolini