Joe Pearce discusses the ethical debate around ‘stop and searches’

Knife-crime is a sensitive topic, one often dividing opinion nationally. To combat gang-wars and possible intent to harm others, police have used ‘stop and search’ tactics as integral to anti-violence operations. Many are for the increased use of these methods, but others argue it does little to solve the real issues attributing to violent tendencies.

According to Gov.co.uk, police officers have the power to stop and search if they have ‘reasonable grounds’ to suspect you’re carrying illegal drugs, a weapon or stolen property. Furthermore, you can be stopped and searched without reasonable grounds if it has been approved by a senior police officer. This occurs when one suspects that serious violence could take place or if you’re in a specific location or area.

In addition to reasonable grounds predilections, officers of the law will also have to provide certain information when carrying out a stop and search. This includes their name and station, reason for search and the legal framework allowing the power to violate personal integrity. Police officers can also ask you to take off items of clothing, but only same-sex officers can ask for more than gloves or jackets during such searches.

Police officers in this sense have enormous power and responsibility to prevent crime, but also to uphold moral obligations to society when displaying such power. Members of disadvantaged communities often feel that the latter of moral obligation is lacking, and that the reasonable grounds premise is seldom justified to carry out such searches. Many feel it only further contributes to disenfranchise young people on racialised lines with exclusionary intent.

Writing for the Guardian, a youth-worker and journalist called Franklyn Addo recalls his experience of a stop and search at the young age of 14. He claims no recollection of reasoning for being searched and believes the officers were “fishing for a sign of wrongdoing”. Reminiscing his feelings, Addo emphasised the sense of shame and fear it induced whilst running a simple errand for his auntie (going to the shop on her behalf, using her purse).

Stories such as this are all too familiar for oppressed communities such as Franklyn Addo’s, who strongly believe race is an important factor for these ‘unreasonable’ searches. Since the first waves of migration in the UK, ethnic minorities have been excessively monitored. They have been classified as innately deviant objects of suspicion, often being physically brutalised in the process.

Giving credence to the belief of race and class as informing ideas of suspicion among certain groups are the statistics. In Dorset, black people were ‘stopped and searched for drugs at 25.6 times the rate of white people without evidence or proportionate result’. According to Stop Watch, this over-policing can be counter-productive and crime-generative in the long term. It is actually delaying the problem by treating the symptoms of social disparity and not the cause of it.

Young people are being rooted out as subjects of suspicion, and not potential victims to be protected. Ethnic minorities increasingly feel unsafe because of gang-related violence and the police obsession to put them under the same vicious umbrella. Not enough is being done to cultivate a safe society. Increased stop and searches only induce shame and ignorance of young ethnic minorities, installing a sense of acceptance in their own character as inherently violent persons.

This insinuation of inherent violence is, of course, not true. Akala, on Channel 4 News, displayed the facts on London knife-crime and highlighted the truth of young black men in the city. He argued how gang violence is nothing new and the social indicators remain the same. This includes poverty, domestic abuse and a lack of education. He explained how out of the 1.2 million black people in London, 50 will kill someone (in a bad year). That is less than 0.004 percent.

The focus then should not be on black people or ethnic minorities as probable criminals, but on systematic defects that produce the social indicators in impoverished areas of London. Even having more police and tougher sentences does not work worldwide. There is no correlation that proves a reduction in crime from over-policing/punishing.

We need to ask why young people feel so desperate, disenfranchised and enraged that they end up killing other people. Increased stop and searches will not undermine or explain this desperation.

For Akala, ‘racial explanations are a way out for the powers that be’. It gives an excuse to higher society to deflect blame and justify expenditure cuts. Akala goes on, stating that money needs to be prioritised by working to end poverty, domestic abuse, sociological and psychological problems.

This means ‘valuing these people in society as important’, giving a much needed and more nuanced view on society. Grassroots community initiatives are necessary to give opportunities to young males, so gangs are not a rational option for them.

This does not mean abandoning stop and searches entirely, indeed they can prevent murders and other crime. The community is more than happy to endorse ‘targeted searches’ among already flagged individuals the police are already aware of.

However, many of these spontaneous searches are not performed on reasonable grounds and enforce racialised stereotypes. If society focused on raising the standards of communities through education and expenditure, more would be done to treat the environment that such violence is born from.

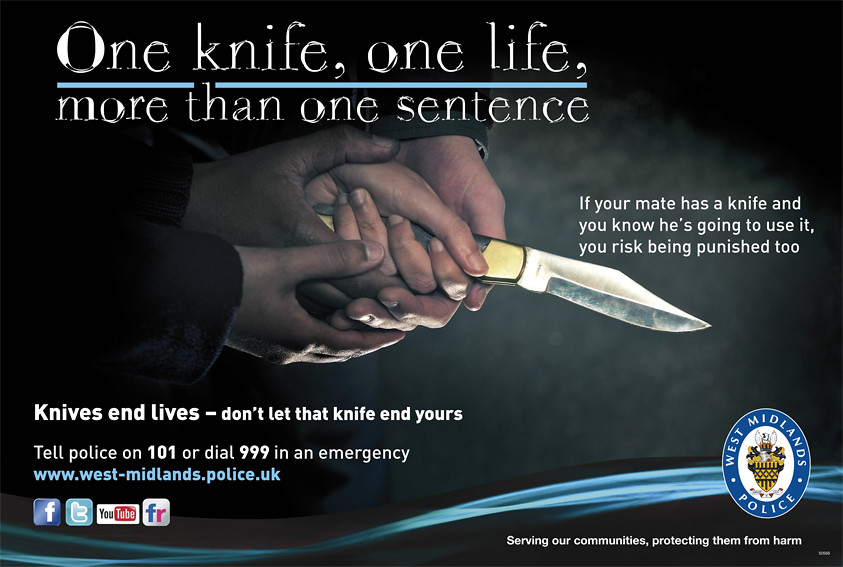

Image credit: West Midlands Police