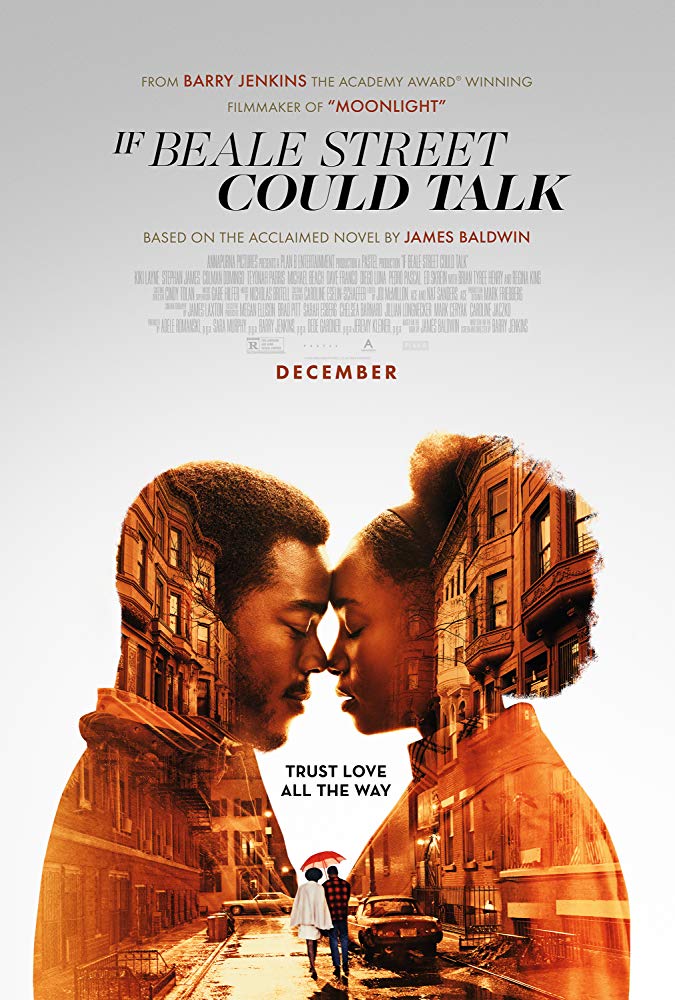

Barry Jenkins describes his latest feature as a series of “memories, dreams and nightmares”. Adapted from James Baldwin’s 1974 novel of the same name, If Beale Street Could Talk follows two young lovers, Tish Rivers (KiKi Layne) and Fonny Hunt (Stephan James), through moments of their childhood and young adult lives. Just as the pair begin to understand what love truly is, they are forced to come to terms with the brutal reality of hate; Fonny is wrongfully imprisoned, stolen away from the person he cares for the most. Told from the perspective of Tish, the book speaks of her inner anxieties and emotions, complexities which Jenkins perfectly portrays on the screen.

This film held me from its opening shot until the theatre lights came back on; for those two hours, very little appeared to matter, other than the fate of the central characters. If Beale Street Could Talk offers an insight into the lives lived by black families in the seventies, the injustices they experienced and the love shared between them; this love is especially highlighted through the performance of Regina King as Tish’s mother, Sharon, who is just as dedicated to proving Fonny’s innocence as her daughter.

Although fictional, Baldwin’s novel tells very real stories; audiences witness an incredible amount of hardship, watching good people fight against a world determined to destroy them, but it’s not just sad, there’s more to it. We see into the Rivers’ home – learning of the tenderness and support they offer each other – we see a black man become an artist, we see the sense of community amongst minorities and we see the – somewhat comical – instances of family drama. The character of Tish’s sister, Ernestine (Teyonah Parris), in particular offers relief from the film’s emotional weight with her bold wit and more optimistic outlook.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N4m3t3G3Zqc[/embedyt]

As Jenkins describes, the story does not follow a chronological narrative timeline, but instead is a collection of Tish’s own personal memories; discussing the film led me to believe that there is no single striking scene, but many heart-warming and heart-breaking singular moments throughout. With a large amount of the book focusing on Tish’s inner monologue, it was up to Jenkins to translate this onto screen and with sound. Much of Beale Street does in fact feel like a sweet dream. He offers the film space – allowing lots to be said even without dialogue. With James Laxton’s careful cinematography, its blue and yellow colour palette and Nicholas Britell’s stunning score, the buzz of the city is mellowed. And so, when they occur, the few spikes of harsh realism are jarring; the tone changes in a split-second and it’s as if these scenes have been plucked from a horror. Although some have claimed to dislike these scenes, I would argue that they’re effective, telling of the unexpected sudden terrors many black people faced (and continue to face) in their everyday lives – showing how sweet serenity can be bitterly stolen. As in Moonlight, the writer-director allows his actors to stare directly into the camera and become the centre of his cinematic universe. Those watching are willed to empathise, seeking any emotion evident in the characters’ eyes. It’s powerful and distinctive, giving his films a sense of self-awareness and emphasising the amount of truth to the stories he chooses to tell.

With the release of another, simultaneously, raw and moving film, Barry Jenkins proves himself to be one of the most empathetic and honest filmmakers working today. Rightfully nominated for the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay, he has brought sound and colour to a well-loved novel.