At the outset, Mr Messier’s FIELD at once invoked The Matrix and Daedalus’ Boiler Room set. The basic concept of this mixed media performance relies on transducer microphones picking up the eponymous electromagnetic field in the performance area. As he plugged and unplugged ¼ inch cables into a patch bay crafted from two metal boards, rhythmic bass synth hits synchronized with his movements. Occasionally, the aural experience seemed an unholy matrimony between incidental music for a modern reboot of the 90s cult classic Hackers and an early Kraftwerk album.

The attendant visual spectacle — which Messier tells us is to be driven by the music rather than the reverse — initially felt like the wooziest part of a bad trip. Shadows of the set scuttered across screen, wires dangling from the metal boards morphed into windmills. As the dizziness subsided, shifting light sources began to evoke Javanese shadow puppetry — Wayang Kulit — but rather than the beat of the kendhang drum, scene changes were signalled by blackouts and booming synthesizers. Equally, these shadows also created the illusion that the patch cables were being plugged into Mr Messier himself, bolstering the sci-fi tenor of the performance.

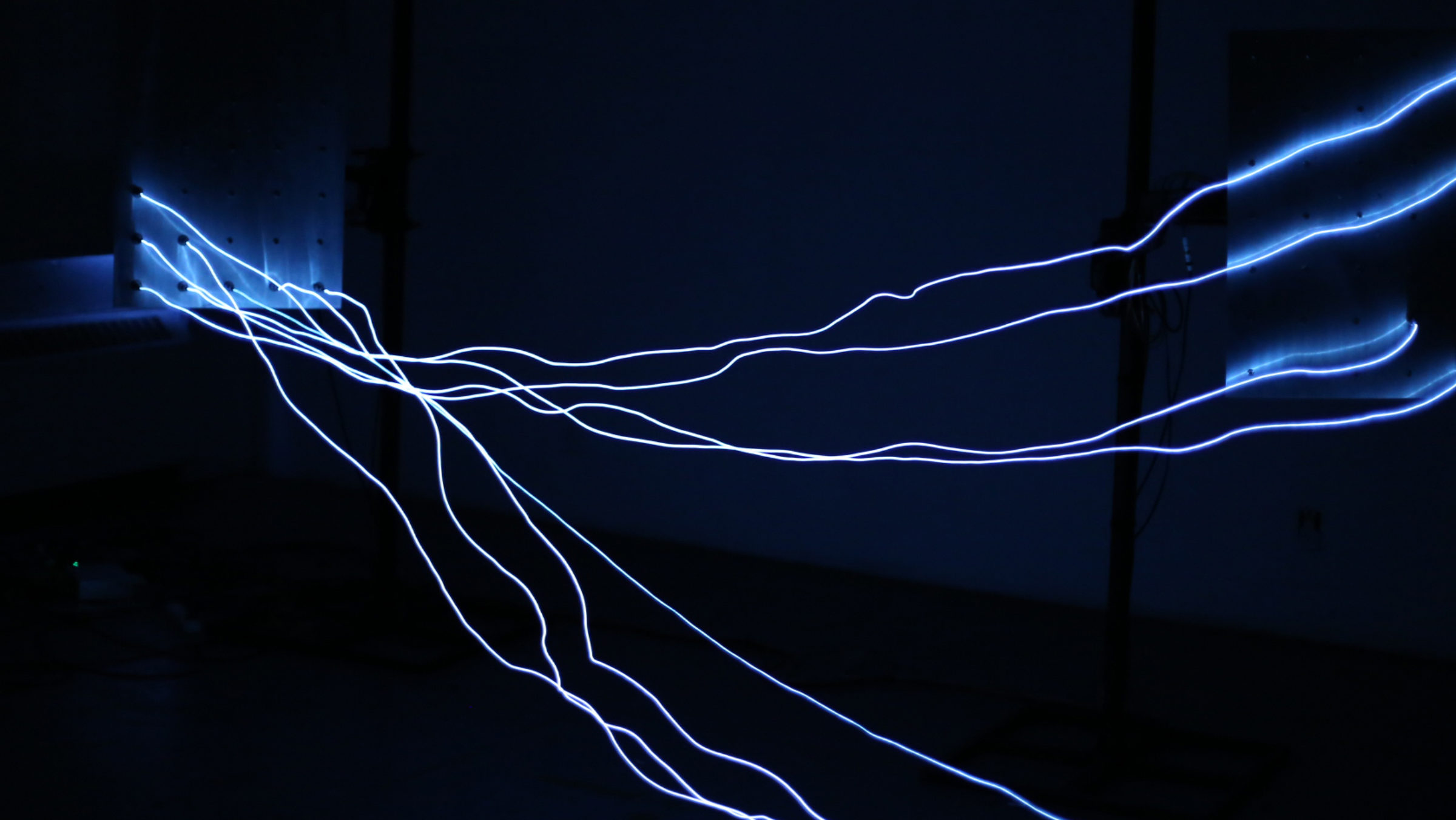

The dizzying audiovisual synchronization climaxed with the introduction of a light show. Patch cables transformed into what looked like an electrical storm. For a few minutes, Mr Messier appeared to bend lightning and the audience was expectedly in awe. Finally, he bowed the patch cable like a violin with strings made from currents. At its best, the show made attendees feel as if they were inside a synthesizer.

The second show of the double-bill featured Grammy-nominated keyboard player Suzanne Ciani. She instead played a Buchla, a modular synthesizer, named after its Californian creator. The term ‘synthesizer’ is itself a bit of a misnomer, given that the sound produced is entirely analogue. Unlike the Moog used in hits such as Kraftwerk’s ‘Autobahn’, there are no familiar keys on a Buchla, no one to one mapping of a mechanical input to a single pitch output. Nor is the instrument simply a vehicle for simple serialism. It is, in Ciani’s words, about controlling and producing a matrix of sound. The heart of the Buchla is a terribly mathematical sounding module called the Multiple Arbitrary Function Generator, which allows the user to control the voltage and timing of inputs. On top of this Ciani adds two H9 Eventide effects pedals for harmonies and echoes. The final result is an intimidating mix of patch cables, knobs, displays and controllers that are unlikely to resonate with the typical understanding of an instrument.

The performance was sonically dense and frankly difficult to understand, but Ciani’s virtuosity was on full display throughout the thirty minute run time. Input pitches were transformed and layered, panning and oscillating to create a remarkable sense of space. The performance might be summed up as peripatetic: this music is not so much about sound as its movement. A projection of Cianni’s setup gave viewers a glimpse of how Cianni monitored this movement through a tonne of LEDs.

Samples, Ciani said in a discussion after the show convened by Dr Evelyn Ficarra, are ‘dead on arrival.’ In this way, the world of modular synthesizers is as much about process as product. She compared working with modular synthesizers to humans; each machine has its temperament, and on the night of the performance her Buchla experienced a bit of a mood swing – although perhaps only she knew this. Through the oscillations, modulations, and reverberations, both Ciani and Messier managed to enthuse, perturb, and ultimately enlighten a packed theatre.

Image credit: ACCA