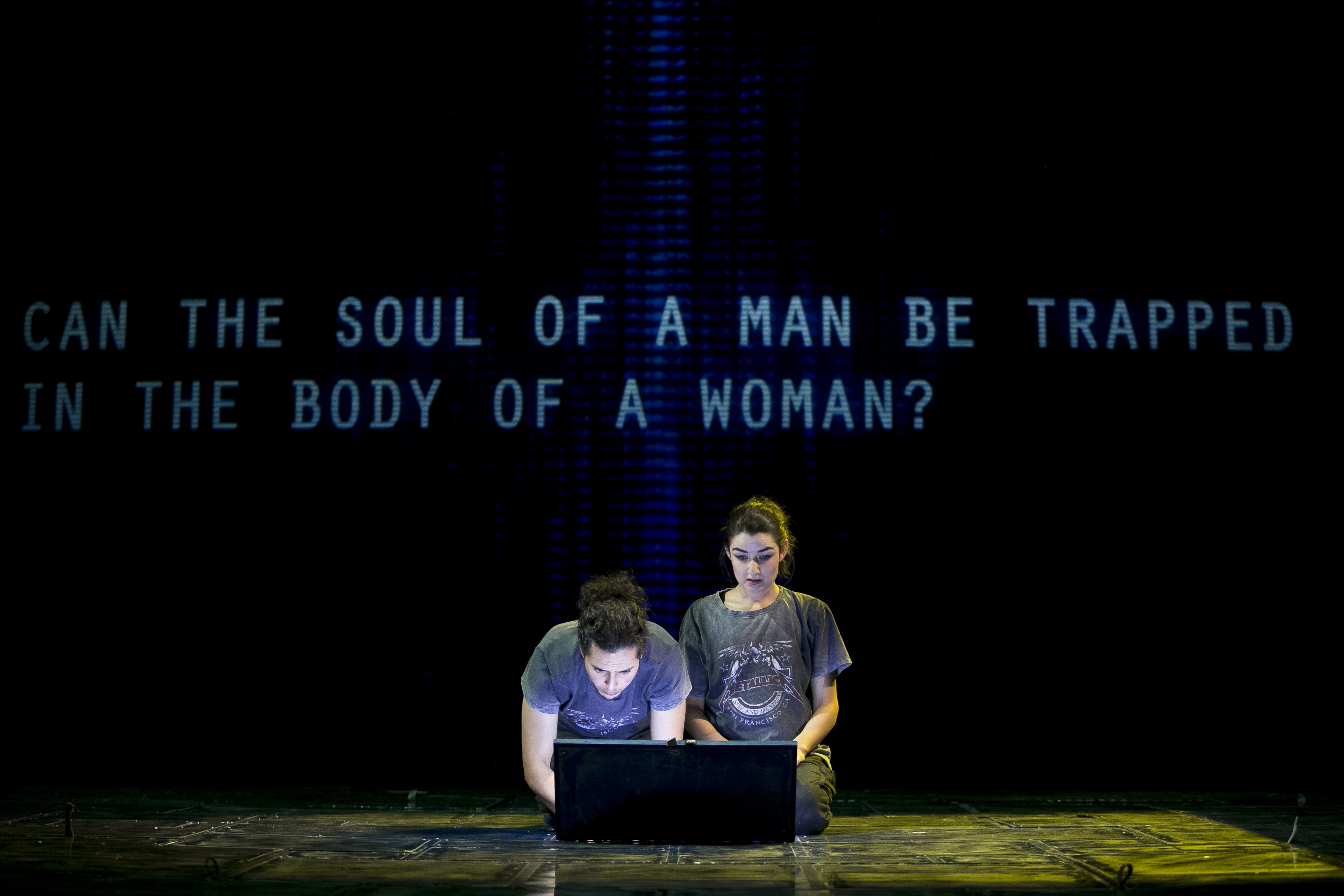

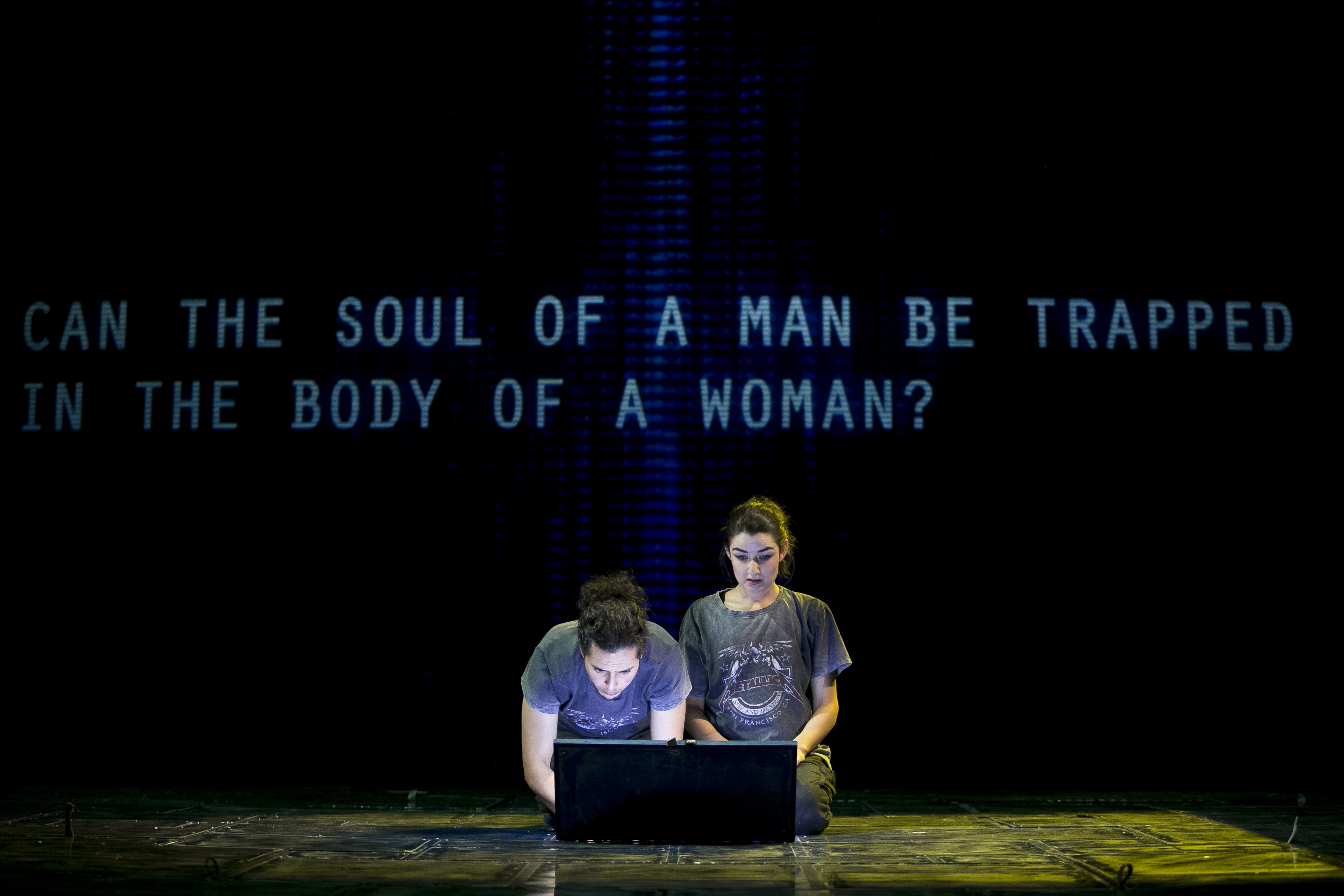

If you have been a stranger to the stage this spring and decide to see one contemporary show, let it be Adam.

This reviewer went in entirely blind. Slowly, as the depressing details of the transgender protagonist’s journey across physical and social borders, it became clear to me that the story was real. The protagonist battles gender dysphoria in Egypt, where expressing his masculine traits and his sexual attraction to women would threaten his life.

The play’s early moments appear particularly light-hearted. Nine Inch Nails and Lady Gaga songs feature prominently, but the heavy subject matter quickly sets in.

Adam discovers the international legal principle of non-refoulement — an asylum seeker cannot be returned to a territory where their life or freedom is threatened — and hopes that this will allow him to escape Egypt and build a life elsewhere. His encounters with the legal process teach a familiar but sobering lesson about how distant sacrosanct principles of international law can be from the lived realities of the vulnerable people they are poised to protect.

Adam is so powerful in part because it may actually persuade a class of older leftwingers — the sort who identify vehemently as activists for all sorts of progressive causes but cannot understand the villainization of Germaine Greere or Peter Tatchell — that trans rights are worth fighting for. The moving depiction of the protagonist’s gender dysphoria and his savage treatment by the Home Office have all the persuasive appeal and little of the animus (if you’ll forgive the Jungian double entendre) that an older generation might expect. By eschewing a brazen and boisterous politics, Adam is all the more powerful. The play ends on a happy note with a revelation that stunned the audience at the Theatre Royal, prompting a standing ovation.

Ultimately, this is a tale of borders and the struggles of those who cross them. It is about the liminality of both asylum and gender; departure from a dangerous situation does not guarantee safe arrival elsewhere; leaving behind the physical vestiges of womanhood does not result in the comforts of masculinity. To borrow a concept from an academic formerly based at our School of English, the play uses the motif of contranyms (words with two opposite meanings, like ‘sanction’) throughout to demonstrate a kind of hybridity — being two things at once is articulated not as a form of liberty, but through the crushing sensation of being awkwardly, dangerously stuck.