Chinese leader Xi Jinping, now the Chinese ‘dictator for life’, has recently banned Orwell’s Animal Farm and 1984 as of February 2018. Some of the more unusual results of Xi Jinping’s bid to set himself up as ruler for life is the unlikely banning of the Letter N. The 14th letter of the English alphabet was another unsuspected victim in Jingping’s peculiar censoring of phrases, words and works of fiction under attack. Alongside these comical bans, the ongoing Chinese joke that Jinping resembles the fictional bear Winnie the Pooh has led to the censoring of images and memes comparing the two figures. The backlash at this decision was met with hostile and satirical social media posts, particularly with stills of Winnie the Pooh side by side with the President himself.

Whilst the news of Orwell’s banning hits headlines, it is by no means the first of its kind. A writer that inspired a catalogue of harrowing dystopian fiction, including Atwood’s A Handmaid’s Tale and Golding’s Lord of the Flies, as well as much of what makes up our literary canon today, it comes as no surprise that Orwell’s fiction has been placed under the microscope more than a few times. His novels, which were strongly influenced by the past and what this meant for the future, speaks to the complicated relationship between humanity and power. Things are never simply positioned in terms ‘black or white’, ‘good or bad’ in Animal Farm. In the narrative, what replaces the old aristocratic regime of Mr Jones is overturned by the animals themselves, as a response to the animal’s inequality to their human masters, they fight back with the slogan “all animals are equal”. Unfortunately, this change in power does not equate to social progress. Instead, the government is re-established through another authoritarian regime, this time under the communist leadership of Napoleon’s group of pigs, where “some animals are more equal than others”. Writing in the politically volatile year of 1943, Orwell found it difficult to publish Animal Farm in the UK primarily due to fears of weakening the relationship with Britain’s ally in the USSR during the Second World War.

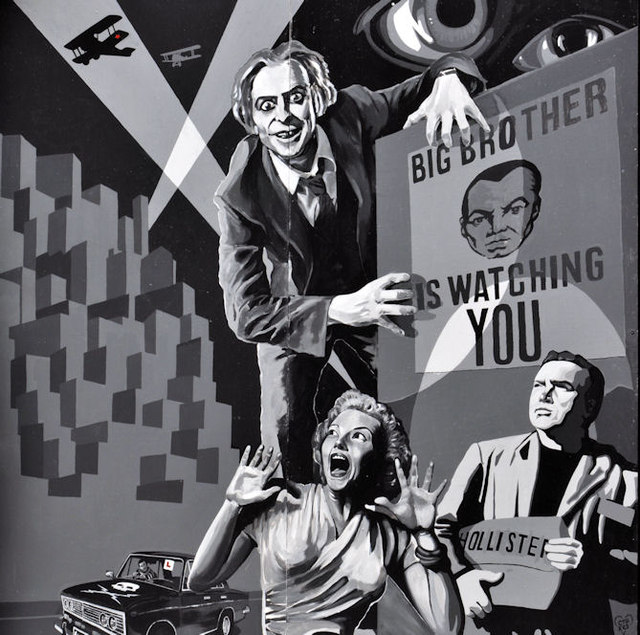

Orwell’s second book 1984 is blunter than Animal Farm; gone are the absurd and docile images of a rural farm, its place now taken by human beings and an extreme version of CCTV. The infamous phrase ‘Big Brother is watching you’ has never rung truer than today, especially after President Xi’s order to put 1984 down the memory hole. 1984, one of the top 10 most censored books to date, has confusingly been banned for complete opposite reasons at different points in time. It was first banned and burnt in communist Russia under Stalin’s rule, and brought a whole new meaning to rebellious reading. Its later history in the United States is both ironic and fitting. Despite 1984 being banned in the countries, it specifically targeted, during the 1960s Cold War period, the UK and the USA nearly banned the book for being ‘pro-communist.’ This just goes to show the ways in which the book can be read and misread.

However, this trend follows more than the works of George Orwell. Across the Atlantic, Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was not always seen as one of the greatest American Novels. Weeks after the satire was published in 1885, the book was rejected by librarians in Concord, Massachusetts on the grounds for it being “rough, coarse and inelegant” and “more suited to the slums than to intelligent, respectable people.” The debate over Twain’s novel was sparked by two major issues, firstly due to the incoherent language and secondly on socio-political grounds. Huck, Jim and Finn and many of the other characters in the novel speak in regional dialect of the south, making it historically representative. The more antagonist voice claims that the derogatory tone of the book towards Southern African American characters is racist. However, despite these claims, what these critics may have failed to see is that it’s intentionally racist – it’s about racism itself. Like with Orwell’s novels, Twain’s writing (whether intentional or not) invites modern readers to assess history through an undistorted, yet nevertheless disturbing lens, seeing as it is, rather than how we may have desired it to be. Viewing the novel in this way, we see that we cannot erase history or its significance.

James Joyce’s Ulysses was another acclaimed fiction once regarded as too radical to read. It saw British and American governments ban, burn and confiscate this ‘dangerous book’, whilst now it’s considered to be a Modernist masterpiece. One consistent trend ensues– in the form of an out-dated idea that with thought-provoking books, reading becomes a weapon. Ironically, similarities can be drawn between the censoring of these ‘provocative’ books and Orwell’s anticipation of the ‘thought-police’.

Unsurprisingly, historically the US and UK alongside the Vatican and just about any other country under the sun are no strangers to the rituals of book banning –just refer to it as part of the rich tapestry of history. While book banning is still apart of everyday life in some countries, the situation is not all bleak. The ABFE (American Book sellers for Free expression) as well as other non-profit organisations aim to challenge book banning in public libraries and schools. Works such as The Kite Runner, Toni Morrison’s prized novel Beloved and The Miseducation of Cameron Post have all been at points in history censored or criticised, only to find resurgence through the ABFE.

Orwell’s works are still held up as some of the most politically clever and controversial fictions to date. Although over 70 years old, they are still as relevant today as they were at their inception. They are timeless in their ideas, with Animal Farm bonding the ridiculous world of farm animals to that of a political state, and with 1984’s prescience concerning freedom of thought and expression. These works continue to ask us to look beyond what we think is right and normal. We can only hope Orwell’s ominous prediction, that ‘if you want an image of the future, imagine a boot stamping on the human face: forever.’, does not follow.

Featured Image: Geograph, Ireland