As it reaches a century since the defining moments of women’s suffrage, Roisin McCormack looks into how much things have really changed. Is a celebration of the time passed since women gained the vote bitter-sweet in reminding us of how much still needs to be done, or can we look at our century of progress with sincere pride?

Amidst the seemingly unending reports of high profile sex scandals, of pay gaps and of everyday sexism, the celebration of 100 years of female suffrage has quietly crept onto our radars.

On the 6th February 1918, under the Representation of the People Act, voting rights were extended to women aged over 30 for the first time.

This was a defining moment in the history of gender equality.

Although limited in scope by today’s standards, only applying to 40% of the women in the country, the act marked the success of a hard-fought, unrelenting campaign by the suffragettes. A decade later all women aged 21 and over were granted suffrage.

Accounts of women chaining themselves to railings, going on hunger strikes, continually protesting and, as in the case of Emily Davison, giving up their lives for the right to vote now seem alien to a generation of gender equality campaigners who (not to take away from them at all) have initiated successful and powerful global campaigns such as #MeToo from behind screens and via the internet.

Of course, the power of protest and activism remains strong: the recent Time’s Up rally in London and others across the globe show this.

While the methods and the aims of campaigning may have changed, there does remain an element of continuity between now and a century ago.

The celebration of a hundred years of suffrage certainly reminds us how far we’ve come: from achieving, by today’s standards, the humbling possibility of voting to having the highest ever number of female MPs in government (32%) and being ranked 49th globally in terms of gender equality. However, the celebration does taste slightly bitter-sweet.

Leader of the Suffragette movement Emmeline Pankhurst stated that “men make the moral code and they expect women to accept it”.

In the age of Weinstein and Trump, her words arguably still have huge significance some hundred years later.

Pankhurst’s own great-great granddaughter having spoken at the Time’s up Rally in London last month showcases this sense of an inherited continuity.

Her grandmother’s statement remains relevant, as women across the globe refuse to concede to a male moral code – one of routine sexual abuse and harassment.

It’s important to remember the suffrage campaign was not solely concerned with votes for women; it was driven by a desire to change people’s attitudes to women.

It has come to light that today, in certain spheres and situations, an outdated and degrading view of women and their bodies persists. We can begin to question whether burgeoning success in democratic rights, on paper, means less when such basic mental attitudes towards women persist in practice.

The motto of the suffragettes was “deeds not words”. With inappropriate attitudes, behaviours and deeds toward women seeming commonplace, even within the very walls where democratic rights for British women were first writ in law, words and laws granting women the same rights as men lose potency.

The work of the suffragettes is to some extent reduced when a strong mental zeitgeist within Parliament, Hollywood, and elsewhere remains firmly rooted in the 1900s, when the fight for suffrage first began.

As the motto “deeds not words” was important during the height of the suffrage movement, used to encourage women’s active involvement, it remains so now in highlighting the blatant inconsistencies between social and legal discourses on gender equality, and actual practices of sexual misconduct and pay gaps.

Clearly, women are still fighting their own battle and share common ground with the suffragettes in their view to correct attitudes about women. This, however, goes hand in hand with the shared experience of facing down critique and adversity.

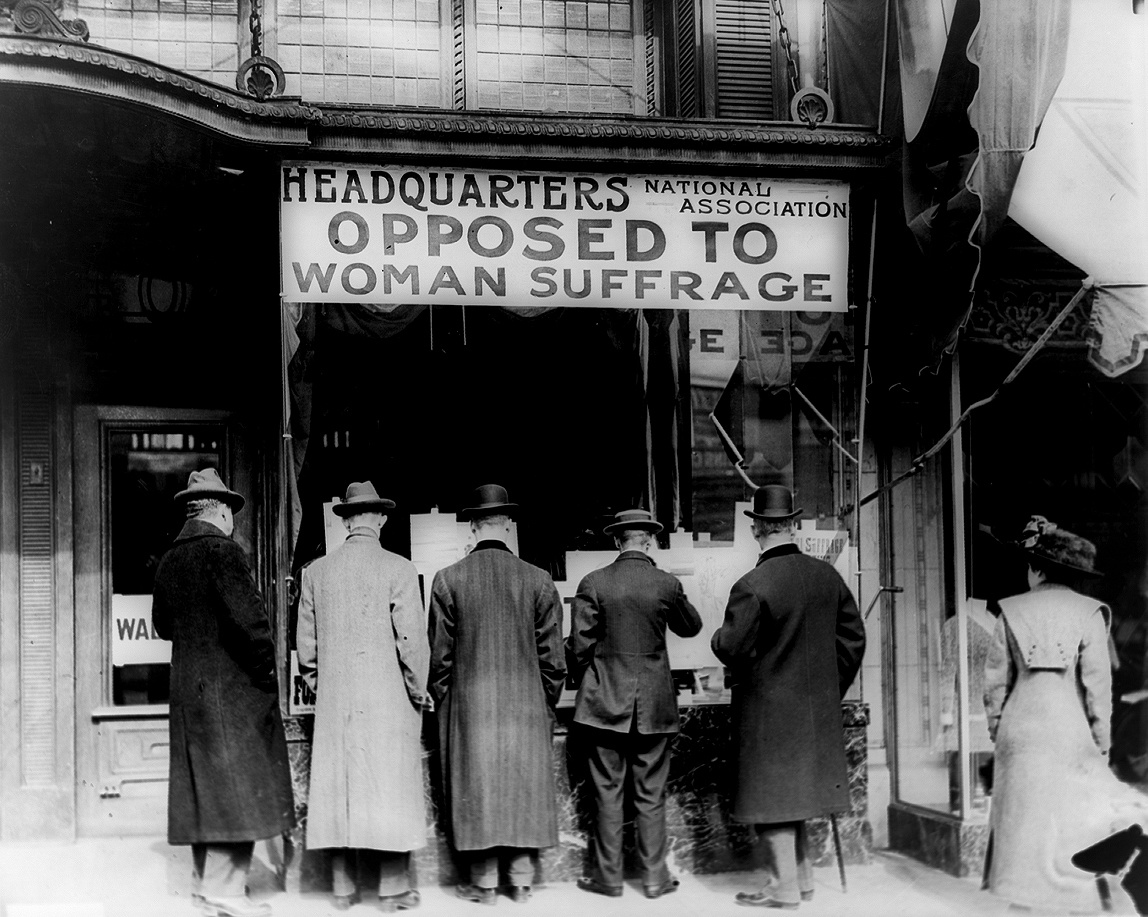

The suffragettes gained their very name from what was meant to be a desultory Daily Mail headline (some things don’t change). They faced fierce opposition from the Womens’ National Anti-Suffrage League, were subject to physical and sometimes sexual abuse during protests, and were often ostracised by family and friends.

Women today and supporters of the #MeToo movement are also being attacked for voicing their opinions. In less extreme ways, of course: but nevertheless their attempts to bring predatory men to justice, and to reassert women’s positions as equals who surmount the role of sex bots, has gained them critique for recreating the Salem Witch Trials, and for (as French feminists and actresses suggested) destroying the art of male seduction.

This latter criticism shares similarities to one anti-suffrage argument that stated granting women the vote would introduce competitive relations between the sexes, and would thus destroy ‘chivalrous consideration’.

Both arguments centre around the anxiety that men might have to change their behaviour and their attitude towards women; that certain moral codes might have to be rewritten.

There remain continuities of a negative kind, ones that we hoped would have been left in yesteryear.

However, an inherited sense of female solidarity, on a truly global scale, is one continuity that Emmeline Pankhurst, Emily Davison and her ilk would have been proud of – it’s just sad that it has become so necessary.

Indeed, within this very continuity of female solidarity lies a discontinuity: one sure to make the women’s movement stronger.

Movements like #MeToo, that are – due to their sheer widespread recognition and support – comparable to the suffrage movement, are no longer centred around white middle-class women.

The Disneyfied image of blonde, blue eyed, middle-class suffragette Mrs. Banks in Mary Poppins no longer fits the bill, as the women’s movement today is far more far-reaching and intersectional in its approach.

Though there still needs to be progress in making this more visible in Parliament (there are currently only 4 black female MPs), suffragette solidarity is evolving to represent our more multicultural society.

Marking 100 years of suffrage is important in recognising the things that have changed for women since 1918- in law, at the very least.

Laws begin to seem futile, however, when it appears the impetus and mindset behind them is half-hearted and non-committal.

The Equal Pay Act of 1975, and other gender equality laws, are made a mockery of, and render the whole system abject, if the principles behind them are not being put into practice.