Yes:

Miles Fagge (Theatre Editor)

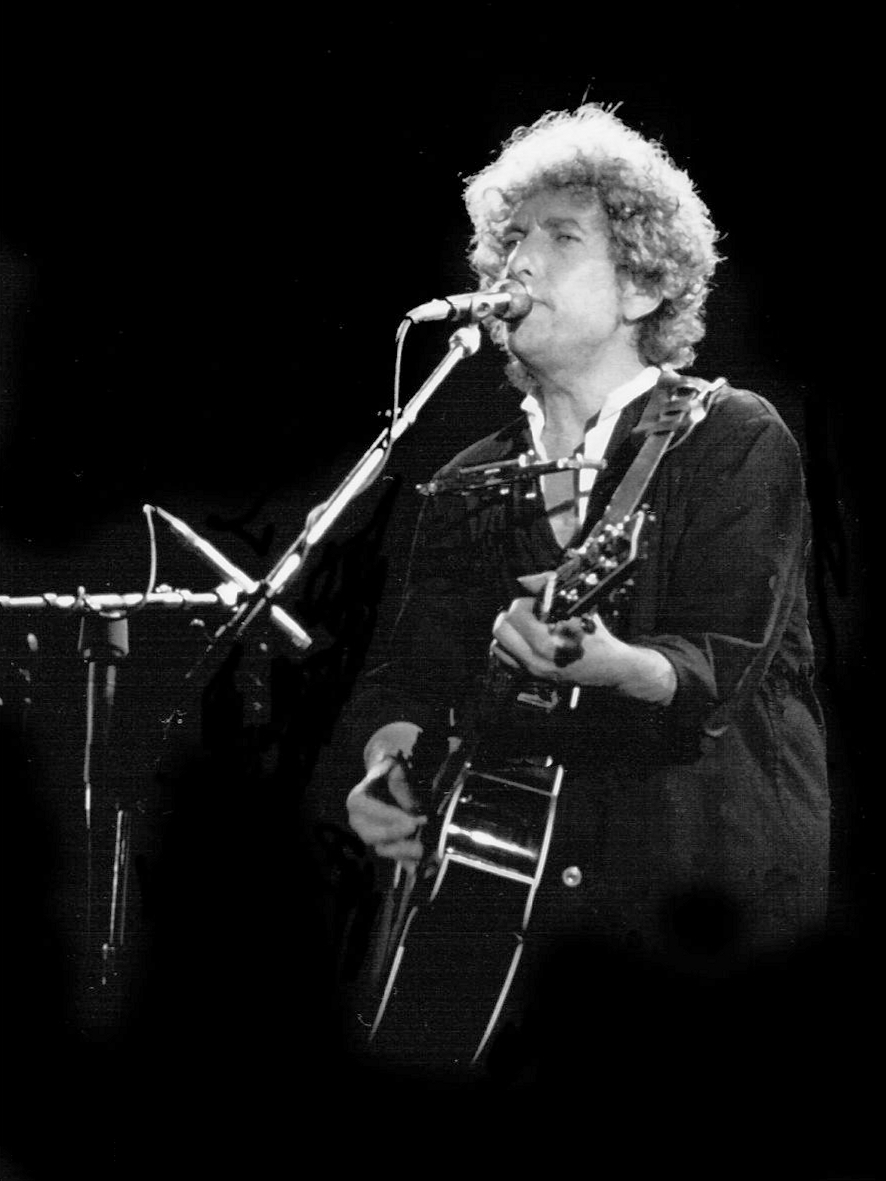

I want to start this by stressing that I am not seeking to argue that Bob Dylan necessarily deserved to win this award more than the others in contention for it. As much as I may love the work of Bob Dylan I don’t have the knowledge of the other potential winners to make that argument, nor is that the focus of much of the criticism of Dylan gaining the award.

Instead this criticism seems to stem from the fact a musician has won the award, specifically a singer songwriter, as if that craft is somehow undeserving of the tag of ‘literature’, and that it cannot be considered in the same league as highly regarded novelists. It is this point of view that I will argue against.

Literature is often regarded as some lofty and immovable part of culture, a constant and a given, but this could not be further from the truth. Our very conception of what literature means is a product of history and of our own cultural moment. This is perhaps best exemplified by looking at the novel as a form, which is regarded by many as the primary literary form and even as the pinnacle of it. This was not always the case.

The novel itself is a relatively recent invention, and was regarded by ‘serious critics’ as a lesser form than that of poetry when it emerged in the early 18th century. It also went through many formal shifts, ranging from serialisation into weekly or monthly instalments (most of Charles Dickens’ work reached its audience this way), two volume novels, three volume novels and so on. The simple Penguin Classic we now regard as the epitome of ‘literature’ is the product of a long and varied history, and it would be naïve to assume this will always remain the standard. I do not wish to bore you with a history of literary forms, but simply want to show that our conception of ‘literature’ and what that tag entails is nowhere near as solid as some may assume.

Indeed, the very idea of the printed word as ‘literature’ is a slippery one. Most evidence suggests that most of the classics including The Iliad and The Odyssey, attributed to Homer, were born of an aural tradition, sometimes even chanted or sung. Likewise, Shakespeare is seen as the archetypal literary great, yet very few of his contemporaries would have experienced his work on the page but instead in the flesh on the stage. So the idea that literature must be locked to a page is a questionable one.

So far I have looked at how literature is not one isolated form but instead a rich and varied discipline, but what links these all together is language. It is this that defines literature for me – the use of language in ways that provokes, moves, entertains and engages. How this language is presented varies, but at its heart it is the power of words to make us feel something. In light of this, Dylan is as deserving of a literary award as anyone else who has ever dived to the depths of language and returned bearing beauty.

Sometimes in songs it feels as if the lyrics are secondary to the music, but Dylan is an example of how the two can be wonderfully matched. I could pick so many of his songs to quote, but one verse that has always stood out is from Mr. Tambourine Man:

“Though I know that evenings empire has returned into sand/ Vanished from my hand/ Left me blindly here to stand but still not sleeping/ My weariness amazes me, I’m branded on my feet/ I have no one to meet/ And the ancient empty street’s too dead for dreaming”.

These words are as poetic and powerful as many great works of literature, just like so many others I could also quote if I was spared the shackles of my word limit. It is wrong to say these do not qualify as ‘literature’ simply because they did not originally reach us in a form we would immediately recognise as such.

I’m a third year English Literature student, and way back in the rosy days of first year, amongst many memories, some of which are admittedly blurry, one from my first proper lecture stands out here. When arriving there was a sheet of quotations awaiting us, and one of those was from Dylan’s Tangled Up In Blue, off the unbelievably brilliant album Blood On The Tracks. The lyrics were:

‘Then she opened up a book of poems/ And handed it to me/ Written by an Italian poet/ From the thirteenth century/ And everyone of them words rang true/ And glowed like burnin‘ coal/ Pourin‘ off of every page/ Like it was written in my soul/ From me to you/ Tangled up in blue’.

These words appearing here next to recognised greats of literature did not seem glib or sarcastic, nor did they seem out of place. It seemed a perfectly apt way to start three years of intensive interaction with literature; these words about loving literature, were in themselves literature. As with so much of Dylan’s work they felt powerful, profound, and well deserving of any accolade handed their way.

No:

Theo Weisz

When I awoke last Thursday morning, I was greeted by a stream of text messages from my parents, siblings and cousins all congratulating me on “The News”. No, I had not passed my driving test, nor had I run a marathon, had a baby or even got out of bed before twelve o’clock. What had happened was that Bob Dylan had been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

As a student whose choice to study English was in large part due to Dylan, I should have been overjoyed that he had been awarded one of the most prestigious prizes in the field of literature, but my feelings were somewhat lukewarm.

Predictably, there have been several articles declaring that he should not have won, the vast majority of which can be summed up as follows: ‘We think Dylan is a really great songwriter guys, but songwriting isn’t really literature.’ This argument conveniently ignores the inclusion of Greek poets Homer and Sappho in the literary canon, whose works were originally written to be sung and accompanied by instruments.

Articles written by self-declared ‘Dylan superfans’ use this title as authority to devalue his literary abilities. I am sure emeritus Professor of Poetry at Oxford Sir Christopher Ricks, who wrote a 500-page book on Dylan’s writings, might have a word or two to say in reply.

Other comment pieces point out that this is the first time an American has won the Nobel Literature prize since 1993 and argue that there are other Americans who should have won ahead of Dylan, as if the prize was some sort of esteemed intercontinental pass-the-parcel.

Criticisms of the Nobel committee’s choice go as far as to say that Dylan was not deserving of the award because he is a white male and, allegedly, a Zionist. The choice is apparently reflective of a society that does not read anymore, but even if that were true, Dylan would be an odd choice, considering that his extensive reading permeates his song lyrics, referencing the Bible, Shakespeare, Keats, William Blake, Rimbaud and Erica Jong, amongst many others.

Bob Dylan should not have won the prize, not because he is unworthy or extraneous, but because he is the antipathy of such an award. While the Nobel committee is often accused of elitism, Dylan is anything but, paying homage in his songs to the homeless, the poverty-stricken and the victims of racially motivated murders, such as Medgar Evers and Hattie Carroll.

While the committee may pander to past Presidents, Dylan sings that even the President of the United States sometimes must have to stand naked. And while the committee may have been short-sighted enough to award the peace prize to Cordell Hull in 1945, in spite of his pressure on Roosevelt to refuse asylum to the Jewish refugees on board the St. Louis, Dylan condemns a similar short-sightedness in his song With God on our Side, in the following verse:

When the Second World War

Came to an end

We forgave the Germans

And then we were friends

Though they murdered six million

In the ovens they fried

The Germans now too

Have God on their side.

The primary reason, however, as to why Dylan should not have won the prize is that its benefactor, Alfred Nobel, founded the prize using the wealth he amassed from manufacturing and dealing in dynamite and armaments. Released in 1963, Dylan’s Masters of War rails against the military-industrial complex. The following verse provides a seemingly pre-meditated response to the receiving of the award:

Let me ask you one question

Is your money that good?

Will it buy you forgiveness

Do you think that it could?

I think you will find

When your death takes its toll

All the money you made

Will never buy back your soul

On hearing that Bob Dylan had won the prize, Leonard Cohen said that giving it to him “is like pinning a medal on Mount Everest for being the highest mountain.” While there are many great writers in desperate need of recognition, Dylan has already achieved the acclaim that most writers could scarcely dream of. He has no need of another award, nor the prize money. So while others might take all this money from sin, or build big universities to study in, let us hope that Dylan does not sing Amazing Grace all the way to the Swiss banks to collect his prize money for an award that could not be more ill-fitting.