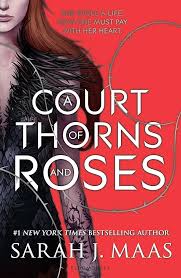

When I was 13, a classmate approached me and recommended I read A Court of Thorns and Roses (ACOTAR). Immediately, I was obsessed! The Tumblr fandom was thriving, the fan art was life-changing, and the characters consumed my thoughts. I eventually forgot about the series until a few years ago, when popularity was resurgent – especially on the TikTok reading community, ‘BookTok’.

I noticed that women, older than myself, were picking it up in stores and raving about it online. There was a newfound emphasis on the erotic scenes in the series, often referred to as ‘smut’ or ‘spicy’ scenes. This resurgence made me realise something: the explicit chapters in ACOTAR – like the infamous ‘Chapter 55’ – were, and still are, inappropriate for a 13-year-old. This raises the question: what is erotica doing in the ‘Teenage and Young Adult’/’YA’ section of bookstores?

First, let’s establish what is meant by the broad categorisation of ‘Young Adult’. Waterstones suggests the cut-off age for ‘Children’s Literature’ is 12, but there is no official age marking the end of the ‘Young Adult’ period. Sources like the Professional Writing Academy often assume that 18 is the upper limit. While there are no strict rules that determine who can and cannot read YA fiction, it sets helpful boundaries for defining the genre’s demographic.

Notably, adolescent development is typically defined as spanning the ages of 10 to 24, making YA consumers a particularly influential demographic for new ideas and experiences. WordsRated reports that 42.9% of YA book buyers are actually over 18 years old. This prompts a debate over what is appropriate to portray in YA fiction – a debate made even more contentious considering that the genre’s intended age group does not match its real demographic.

One factor that may attract older readers to YA fiction – particularly in series like ACOTAR and Fourth Wing – is the graphic sexual scenes. These scenes have become major topics on social media, with BookTok influencers rating the ‘spice’ levels of a book as a review technique. And yet, these books are marketed towards developing adolescents, who likely have limited knowledge of sexual themes. YA books need to provide a safe space for such readers to ‘explore’ and learn from fiction, whether that is about life experiences or sexuality specifically.

However, the ‘smut’ in these books is often written unrealistically and graphically for a sexually inexperienced audience, who may go on to view these scenes as a realistic depiction of adult sexuality. Similarly to how teenagers can be detrimentally affected by visual pornography, the same applies to the written form. The erotic content in these books is crafted to enhance the story, set up meticulously by the author to ensure an exciting reader experience. A little critical thinking generally allows us to understand this – it is fiction after all! Yet, a younger reader – potentially as young as 12, given that smut is featured in YA – may not grasp that these scenarios do not reflect real-life experience.

Alongside the rise of smut in YA fiction is the increasing popularity of the relatively self-explanatory ‘enemies-to-lovers’ trope. In this dynamic, characters begin as enemies, then gradually become lovers over the course of the story. Arguments and tension are central to this trope, and this feature often bleeds into the sexual activity of the plot, with sexual encounters frequently representing the romantic climax. However, as seen in Fourth Wing, this leads to the actual description of sex being done so in a superfluous and almost violent way.

The lines of consent can easily blur. The visual porn industry is already causing boundless damage, both for those involved in its production and consumers. The former is tied with physical exploitation, while the latter normalises brutal sexual encounters. Moving to written pornography, which is certainly not as dangerous as its counterpart, it is important to remember exactly what is being consumed and by whom. WordsRated suggests that 82.5% of romance fiction readers are women. This risks normalising – even romanticising – borderline abusive behaviour through fictional sexual encounters, especially in books aimed at young, vulnerable readers. The problem, while nuanced, has the potential for significant real-world consequences.

While sexual exploration through media is not inherently negative, it must be remembered that there is a time and place for graphic written erotica. I would argue that that place is best not in the reach of unsuspecting, impressionable children. The TBR list can wait!

Another article you may enjoy: https://thebadgeronline.com/2026/01/what-is-the-environmental-footprint-of-reading/