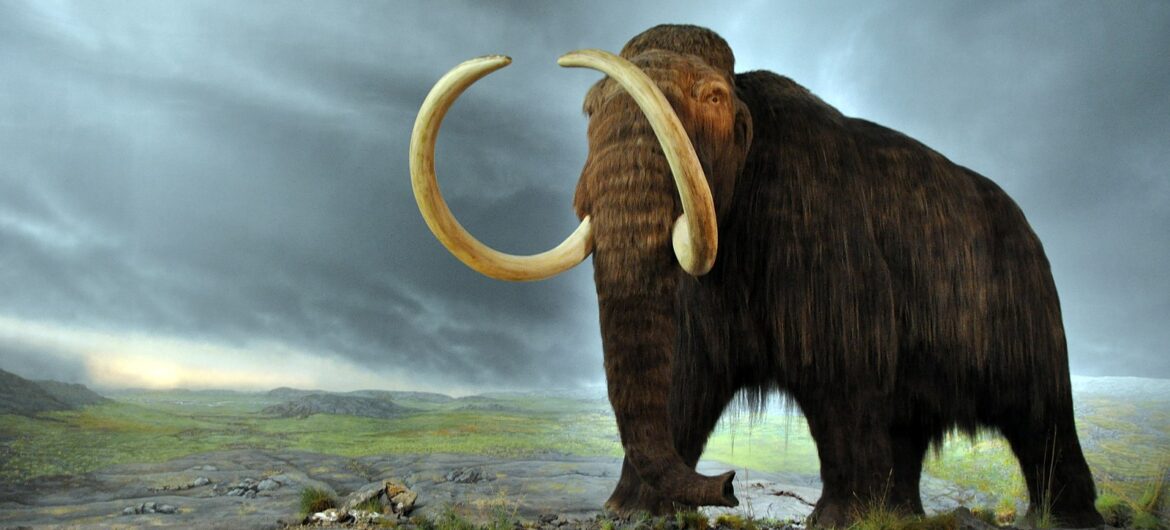

Plans to bring back an extinct giant are creating great excitement, but is it justified?

words by Rob Barrie, Science and Technology Editor

Not for 10,000 years has the woolly mammoth traversed the Eurasian steppe, but a new rewilding project plans to change that.

The extinct relatives of today’s elephants boasted well-known traits to survive the harsh conditions of the Ice Age and there is palpable excitement within the scientific community about the reintroduction of one of the most famous extinct species. Opposition, however, both from within science circles and reproductive ethical groups, have questioned the consequences of such a man-made intervention.

The project, which recently received a $15 million fund, plans to utilise cutting-edge genetic technology. Organisms that are suspended in ice have preserved DNA intact within the genome – the entire genetic information for an organism. The project would involve extracting the genome and cross referencing it with DNA from the modern-day Asian elephant, to identify mammoth-specific genes. Such genes would be responsible for the cold adaptations such as the famous mammoth hair. These genes are then spliced and then inserted into the elephant genome via an isolated skin cell.

Scientists on the project are clear that the reintroduction of mammoths is not for public appreciation or to ‘undo’ the action of humans – after all, it was human hunting that greatly contributed to their extinction. The goal is that with the introduction of herds onto the Arctic tundra, foliage might return to the desolate landscape. By grazing, knocking down trees and promoting soil fertilisation, it is hoped that this will slow some of the consequences of climate change in the Arctic region by thawing permafrost.

Other scientists have been more critical, especially geologists and evolutionary geneticists. Love Dalén, professor in evolutionary genetics at the Centre for Palaeogenetics in Stockholm, voiced his scepticism: ‘here is virtually no evidence in support of the hypothesis that trampling of a very large number of mammoths would have any impact on climate change, and it could equally well, in my view, have a negative effect on temperatures.’

Indeed, whilst the debate about the effectiveness of the project rages on, there is growing concern about the justifications of undertaking such a reintroduction in the first place. Beth Shapiro, a paleogeneticist at the University of California, has previously said it will be difficult to recreate a species that is completely the same as one that thrived 10,000 years ago. There is a feeling amongst zoologists that such genetic manipulation would be more beneficial if applied to living species under threat of extinction such as the giant panda and rhynosaucerous.

Regardless of where resources might be better directed, the question of why humans should revive mammoths pales in comparison to the question of if. Evolution is a complex and natural process that occurs over millions of years. The mammoths became extinct not just due to human activity but also because of the natural warming climate. Whether reintroducing them onto the planet is the ethically correct thing to do is a debate that will long continue. A debate that has marked importance when one considers the human reproductive applications of such resurrections. For now, the woolly mammoth remains a giant of the past, but in six years they might be roaming the tundras of our modern-day planet.