One hundred and seventy years after the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood first exhibited their paintings, London’s National Portrait Gallery are celebrating the divine feminine muses of this historic art movement this Winter, in an exhibition of the Pre-Raphaelite Sisters.

Until the end of January, the Wolfson and Lerner Galleries have dedicated their space to the female models, mothers, artists and lovers of the most influential art movement in British history. Detailing the extraordinary lives and works of twelve women, the exhibition hosts a section for each, including the ethereal muses, Effie Gray Millais, Elizabeth Siddal, and Christina Rossetti. From Gabriel Rossetti’s famous painting of the Annunciation, Ecce Ancilla Domini! (1849-50) to William Holman Hunt’s Il Dolce far niente (1874-5), the exhibition showcases some of the most classic, beloved works of the period – by man and by woman – as well as unseen pieces, including preserved poetry manuscripts by Christina Rossetti, and an original bodice worn by Joanna Boyce Wells.

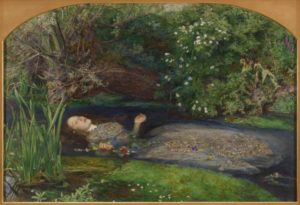

A prominent aspect of the exhibition, as well as a particular highlight, is the focus on Elizabeth Siddal. Tall and pale, with a pronounced overbite and flaming red hair, Siddal was not considered conventionally attractive at the time. However, her tragic depiction in John Millais’s Ophelia (1851-52) as Shakespeare’s doomed female protagonist of Hamlet, fashioned a new concept of beauty. Although the original painting of Ophelia is not on display in the exhibition, a tiny replica is in its place, which is so small that one has to get very close to it in order to begin scrutinizing it. Siddal’s other modelled depictions are also present, including the lavishly gold and almost Devotional painting of the Regina Cordium (1860), and other such delicate drawings by the likes of Rossetti and Hunt. Siddal’s own artistic endeavours are also present: a collection of her poetry manuscripts, which were exhumed from her grave by Rossetti several years after her death, can also be viewed, accompanied by a small collection of her own drawings and paintings.

Although this is an exhibition which celebrates the rising liberation of the nineteenth century woman and her creative and beautified influences, one of my only critiques surrounding the display’s curation is that the power of the male gaze still remains impenetrable throughout. Regarding Hunt’s The Awakening Conscious (1853), a young woman, who was modelled by the artist’s girlfriend, Annie Miller, is seen rising from the lap of a man, her gaze transfixed beyond a window which is depicted in a mirror behind her. Although her thoughts are far removed from the man beneath her, her body language implying her need to get away, the man from behind holds a tight grip around her waist, evoking the limitations of her yearning liberty. Perhaps there is no way, after all, that the male gaze can be removed – perhaps it is inescapable, and is therefore necessary for the exhibition curators to capture this; a way for viewers to grapple with the idea that women still had limitations attached to their freedom, and that art may have given them an escape from the confines of their repressed occupation.

Regardless, the artistic and creative freedom of the woman is still a huge matter of celebration throughout the exhibition, especially so towards the end. The display finishes with the brilliantly vibrant painting of Night and Sleep (1878), which is set upon a tremendously large canvas dominated by a strong palette of pinks and whites. Depicting the dark-haired female figure of Night guiding her son, Sleep, across the landscape, the subject matter evokes the undermined power which women possess, strengthened only by the fact that it was also painted by a female Pre-Raphaelite artist, Evelyn de Morgan. Furthermore, the painting’s place at the end of the exhibition, plus the additional works created by other female artists throughout, signals the triumph of the woman and their own works, their own strengths and their own creativities which are on par or, if not of a higher merit, to their male contemporaries.

Conclusively, the women’s vital contributions to one of the most influential art movements in British history comes as an inspiration, for using their beauty and their creativity as a way of evoking freedom in an otherwise largely repressed period for the Victorian woman. The Pre-Raphaelite Sisters exhibition is refreshing: it’s so very rare for a male-dominated art movement to be viewed through a feminine lens. With a dignified and respectful curation, the National Portrait Gallery has given these unique and, often fallen women, a platform which raises them as an equal to the male artist himself. Behind or in front of the canvas, the exhibition itself pays homage to the Pre-Raphaelite sisters’ critical influences, whilst also celebrating the power of what they possess, both in beauty and erudite, which has continued to pave the way for future artists and movements to come.

17th October 2019 – 26th January 2020

Tickets: £18-20 / £17-£19 (Concessions)

Students get £5 tickets on Fridays only

Words: Grace Sowerby

All photo credits: Grace Sowerby