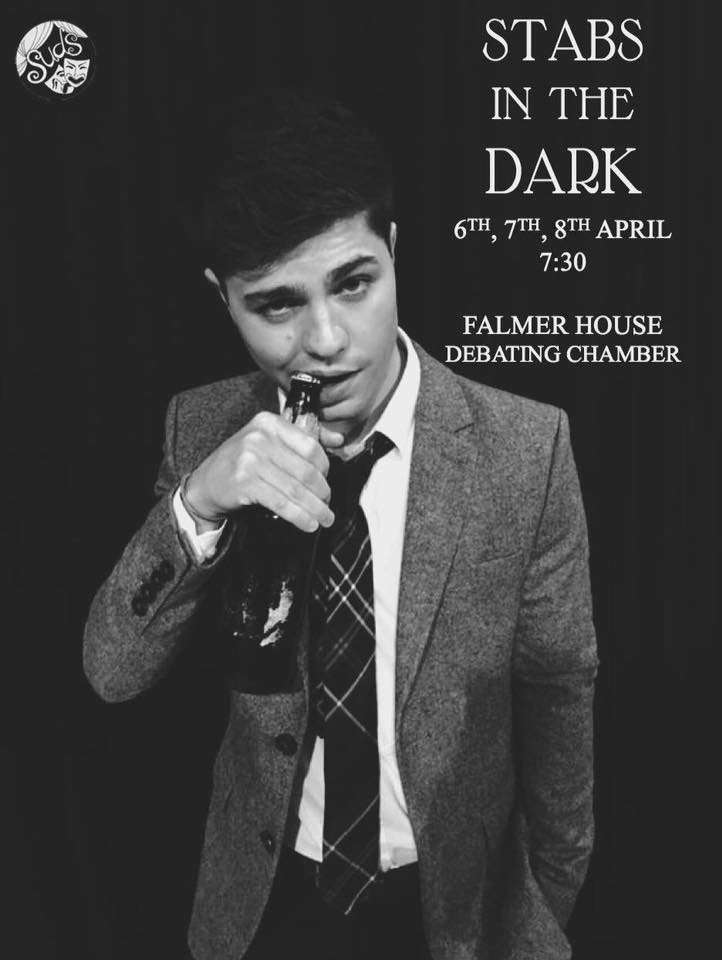

Taken on a whirlwind of vignettes, Stabs in the Dark from director Ka Wei Chan and producer Maddie Holderness is the perfect title for a play that penetrates that fragmentary nature of an alcoholic’s mind.

The trigger for protagonist Ernie (Tom Howarth)’s descent into alcoholism is presumed to be the passing of his sister, Daisy, fifteen years prior when he was only twenty-one. However, this fact is not revealed until toward the very end of the play.

Yet, an initially tragic moment proves to be balanced by the introduction of Rosie (Gemma Hoare), his eventual wife, as they go on their first date in a café not long after the fatal incident.

The first scene depicts Rosie having to walk in on Ernie during the night passed out on the floor in what the audience realise is a regular occurrence within the couple’s home. Her inability to understand why he’s not only abusing himself in such a way but her also leads the audience to sympathise with a wife who has reached the end of her tether after years of selflessly trying to help her husband overcome this disease.

She finds a sliver of respite, however, in the jibe she strikes him in reading an article which says that alcoholic partners are far more likely to abuse their partners. Her proclamation falls on deaf ears, though, as Ernie emotionlessly repeats that of course he still loves her.

Ernie’s job as a detective proves to not bring much happiness either.

His boss and lower-ranked colleague he knows not the names of and instead refers to them by the rank they hold in relation to him. Fellow employee Junior (Triana Townshend)’s mixture of frightful apprehension and tiredness of his antics – defecating on her desk being one such instance – is representative of the balance which the main character so clearly needs in his life.

The caring nature of Boss (Sage Beckingham) evokes sympathy from the audience especially as he gives him chance after chance whilst realising his employee has become increasingly errant over the years.

However, by far the most tragic scenario that unravels in this relentlessly helpless succession of vignettes is the murder of Rosie. Thought not explicit, the evidence builds up against Ernie; the place in which she was shot being his favourite bar, the person thought to have done it presumed to be romantically involved with her.

Not only is her brutal passing sad in itself, the realisation on Ernie’s part that he might be the one responsible leads to him to end the life of destruction he leads. As dark a view as it may seem, the protagonist’s finishing himself in much the same way symbolises the compatibility the couple probably once had.

Ultimately, the scattered, non-linear manner in which the scenes are portrayed seemed rather fitting for the ethos of the play.

Olly Lugg

Theatre Editor