Exposed

When I worked at a pub, there was a man who used to come in regularly – older, loud, too confident. The kind of man who thought everything he said was just a bit of fun. One night, as I walked past him in a cami top, he laughed and said, “Put some clothes on!” Another time: “Bet those help you behind the bar.”

Each time, I laughed awkwardly because that’s what you do, you laugh, so it isn’t weird. But inside, I felt small, bare, humiliated. The words seeped into me, causing the kind of discomfort that sits just under the skin. The effect of his voice landed like a weight in my chest. I froze. My heart pounded. My stomach twisted. The next time he came in, I’d feel myself tense. I’d pull my top higher. I’d avoid the side of the bar he liked to sit at. But no matter how much I covered up, it didn’t make a difference. I was still exposed.

I remember thinking, Why should I have to carry that? Why was I the one shrinking under the weight of someone else’s words, someone else’s gaze? Once again, I had been reduced to the size of my breasts. Someone who saw me every week could only see me as an object for his viewing rights.

Early Lessons

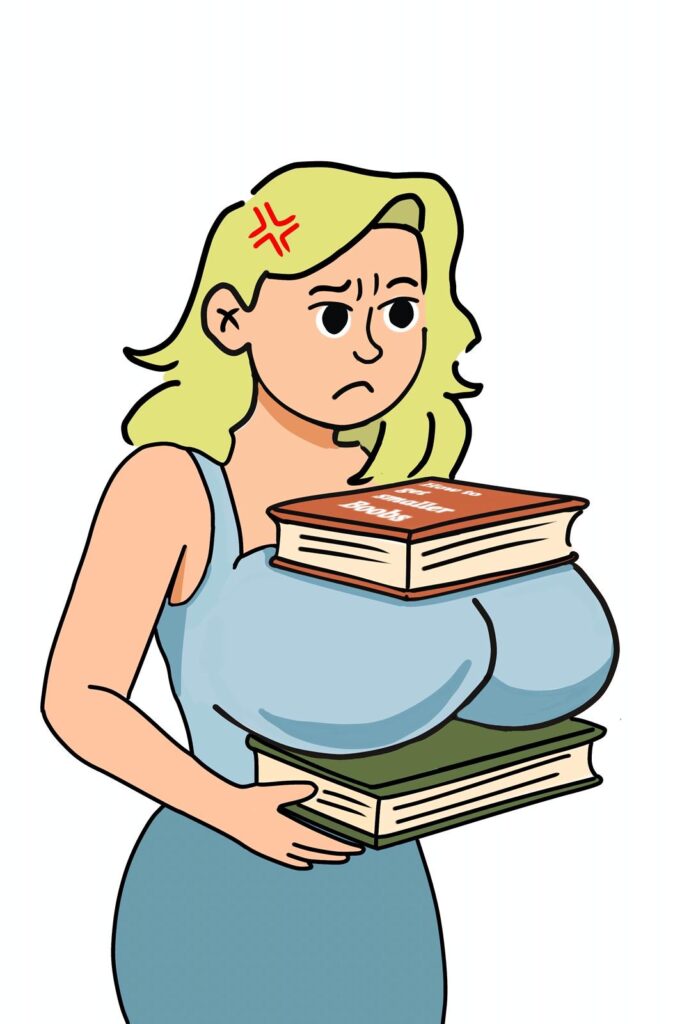

It isn’t just the big moments that make the most impact. It’s the accumulation. It’s when I’m speaking in a seminar and the boy sitting opposite me is staring at my chest. It’s the comments you hear whilst walking past groups of men. It’s the way I pull my shirt higher or cross my arms without thinking. Regardless of what you wear or how you look, you can never sufficiently defend yourself from objectification.

It’s the invisible weight that I can’t carry anymore. Whilst the back pain and raw skin under my bra hurt, it’s the psychological torment that creates the most damage.

I learned early. When I was in year six, I overheard that a group of boys were “ranking” the girls by who had the biggest boobs. My name was first. I remember pretending not to hear. But that night, brushing my teeth, I looked in the mirror and realised something had changed. My body had stopped being mine. The reflection staring back at me felt smaller, tighter, defined by other people’s eyes instead of mine.

The Weight of a Body

A few months ago, my friend from University invited her friends from home to come down to Brighton. We spent the evening at the beach, eating pizza, drinking, and debating whether or not to go to Pryzm. Instead, we opted to go swimming. The sea felt safe. I was chatting to one guy while watching the moon shimmer on the sea’s surface. Slowly, his friend swam over. Out of nowhere, he said, “Issy, do they help you float?”

The joke wasn’t funny, and this time I wanted to make him hear it. I told him it wasn’t appropriate. I felt anger. I felt humiliation. I felt the look on his face when I meant what I said. It felt like a crack in the routine, but the routine is heavy. It will keep repeating.

The Worst Part

The worst part is when the objectification is acted upon. When it stops being looks or words and turns into touch, it’s the multiple times I’ve been groped on a night out by strangers, hands that come out of nowhere, bold and entitled. They always seem surprised when I push them away – as if I’ve committed the real offence by saying no.

I Don’t Hate My Body. I Just Want It to Feel Like Mine

I long for those summer days when I was young – swimming shorts on, chasing my brother across the beach, back when my body was just…a body. Before puberty, I moved through the world just as he did; now, the same body feels like something I’m expected to cover, explain, and apologise for.

When I see women like Sydney Sweeney or Scarlett Johansson, it doesn’t comfort me. It confirms what I already know. That society will always see a woman’s chest before looking any further.

I want to exist without having to explain myself. Without having to make other people comfortable about what they’ve made me feel. When people say, “You’ll miss them,” I think: you have no idea what it’s like to live with something everyone else thinks they’re entitled to. To have strangers decide who you are before you’ve said a word.

This isn’t about loss. It’s about the removal of weight, of judgment, of noise. It’s about finally being able to walk into a room and not be seen before I’ve spoken.

If you’ve been affected by any of the issues discussed in this article, support is available. You can reach out to Samaritans via their website: https://www.samaritans.org/how-we-can-help/contact-samaritan/talk-us-phone/