There is a particular kind of woman who appears, again and again, in literature: beautiful, untameable, and mad. She is Bertha in Jane Eyre, confined to an attic. She is Ophelia, floating dead in a river. She is Esther Greenwood in The Bell Jar, sedated into silence. She is unnamed in The Yellow Wallpaper, hallucinating a woman crawling behind her bedroom walls. She is haunting, tragic, and, crucially, she is always too much.

From Shakespeare to Sylvia Plath, literature is filled with “mad women” women whose mental distress is aestheticised, romanticised, or pathologised, depending on the needs of the plot. But what does it say about us, about our cultures and our stories, that madness is so often the default literary ending for women?

Even in novels written by women, female characters are frequently depicted as psychologically unstable. This is not to say these authors lacked awareness; on the contrary, many used the trope to critique the rigid expectations placed on women. Yet, the repetition of the madwoman figure raises the question: why does womanhood, in literature and beyond, seem so frequently incompatible with mental stability?

One of the most iconic examples is Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper,” a chilling short story written in 1892. Its protagonist, a new mother suffering from postpartum depression, is confined to a room and forbidden from writing, thinking, or working. Diagnosed with a “slight hysterical tendency,” she is subjected to the infamous “rest cure”, a real-life medical practice that saw women’s autonomy stripped away in the name of care. As she slowly unravels, she sees a woman trapped inside the wallpaper, crawling desperately to get out. Her madness becomes a metaphor for the suffocation of patriarchal medicine.

Photo: Alex E Clark

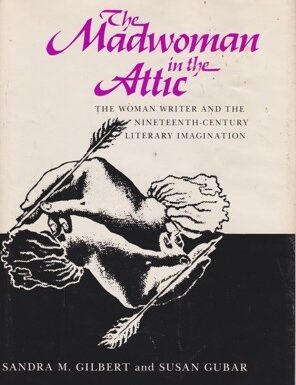

Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre offers another infamous example. Bertha Mason, the so-called “madwoman in the attic,” is portrayed through the gothic lens as monstrous, feral, and sexually deviant. She is the secret wife, hidden away, the literal embodiment of everything a Victorian woman was told not to be. And yet, while Bertha rages in confinement, Jane is locked in the “red room” as a child, a punishment that mirrors Bertha’s fate and foreshadows the narrow path available to women. You either obey, or you’re mad.

Even Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, often seen as a feminist milestone, carries the weight of this legacy. Esther Greenwood’s descent into mental illness is painful, raw, and brutally honest. Based partly on Plath’s own life, the novel charts the impact of societal expectations, sexual repression, and alienation on women’s mental health. She is not romanticised, but she is still institutionalised, electroshock therapy and all. And while we see her begin to recover, there is no ignoring how easily women were discarded by systems meant to help them.

Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye adds yet another dimension, one that forces readers to confront the intersection of race, gender, and mental health. Pecola Breedlove, a young Black girl who internalises racist beauty standards, experiences a psychological breakdown after repeated traumas. Her “madness” is not gothic or metaphorical; it is a devastating response to systemic violence. Morrison’s portrayal is a direct challenge to the idea that madness is merely individual tragedy; it is a collective failure.

This literary obsession reveals deeper, gendered ideas about mental illness. Historically, diagnoses like hysteria were used almost exclusively against women, often to control those who refused to conform. As documented in research such as the University of Louisville’s exploration of “female hysteria” in 19th-century literature, madness was medicalised misogyny. Women’s emotions were pathologised. Resistance became a symptom.

We must ask: Why is it still so easy to call a woman crazy?

In recent years, there has been a push to reevaluate these characters, not just as cautionary tales or plot devices, but as women crushed by impossible standards. Maybe Bertha wasn’t insane. Maybe Esther wasn’t broken. Perhaps the woman in the wallpaper was right to claw her way out.

The figure of the “madwoman” invites empathy and scrutiny in equal measure. She reflects on how far we’ve come and how far we haven’t in understanding women’s mental health. She is a reminder that expressing pain is not a pathology. That women’s suffering is not a spectacle. And that, perhaps, the madness was never in the woman, but in the world she was forced to live in.

Another article you may enjoy: https://thebadgeronline.com/2025/05/in-conversation-with-emma-jane-unsworth/