This year I hosted my first ever Oscars party. The living room was turned into the Dolby cinema, a towel was laid down for a red carpet, and at least three people adhered to the ironic black tie theme. The night went off without a hitch and passed easily, sort of.

‘Problematic’ was the buzzword among my party’s guests. Film fans are notoriously solid in their views and, with this knowledge, a flatmate and myself drew up a secret bingo card of different issues we thought members might argue over. It turned out that, despite each attendee’s love of cinema, harboured in everyone were different degrees of disdain for the individuals, institutions, and artworks that make-up Hollywood. They were bickered over for the duration of the evening.

The party guests represented a specific demographic of Hollywood cinema’s viewership. Being in Brighton, at Sussex Uni, the guests adhered pretty much wholly to a left-wing political leaning, some more militant than others. While left-wing policies do not necessarily present an issue for Hollywood, I would posit that freedom of expression, combined with the egocentricity that social media creates, does.

This year’s Oscars were characterised by extensive meddling from lobbyists and the public, as well as from industry professionals. The months preceding have been clogged with an almost breathtaking succession of announcements, uproar, and U-turns that saw the Academy, in despair over their ratings, struggling to manage an increasingly vocal viewership.

The first announcement was of Kevin Hart as host. Following the revelation of homophobic comments made a decade before, public outrage lead to his resignation, which in turn resulted in Ellen Degeneres – one of Hollywood’s most powerful gay women, and former host – campaigning for his reinstatement.

After this, and in light of Black Panther’s explosive cultural impact, the desire to address past notions of inequality (highlighted in the #OscarsSoWhite movement) resulted in the academy’s announcement of an award for Best Popular Film. This suggested the uneasy notion that popularity and quality were disparate elements of filmmaking, simultaneously undermining the entertainment value of supposed “serious” film, as well as the artistic merit of “popular” film. The ensuing backlash lead to the withdrawal of the plans.

Finally, and at the eleventh hour, the announcement to present specific awards such as Cinematography and Make-Up during ad breaks lead to an uproar from fans, filmmakers, and another U-turn that saw Oscar disconnect his landline, change into his pyjamas, and curl up in bed to weep. Such public contempt for something so historically revered must be challenging for organisers; having to navigate mines in what was once their garden, the loss of control over the media and viewing public has lead, in this century particularly, to rewards being given to questionable candidates.[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hy8z_Tq_VHo[/embedyt]

The ways of criticising this year’s Best Picture nominees were multifarious and of varying significance. Those who watch the Oscars are approaching film from different perspectives. While some are watching to evaluate the artform, others consider it a cultural event. While some see the Academy as a propaganda machine for the left, others view it it as a capitalist behemoth. In short, one may consider the films nominated from varying social, national, cultural, and artistic points of view. With so many factions, and a single method of expressing dissatisfaction, editorial decisions are bound to be attacked from all sides. In light of ratings, it is down to the Academy to pick a Best Picture that upsets the least, and has little chance of damaging its name.

The Oscars are inherently political, and politics holds a bearing on the decision of who wins as much as artistic merit. Despite it’s unbelievable popularity, in a post-Me Too landscape, Bohemian Rhapsody was out of runnings from the first allegations against Brian Singer. After the withdrawal of his Best Director nomination, and an assured acknowledgment with a certain win for Rami Malek, the film stood for Best Picture merely to honour the producers.

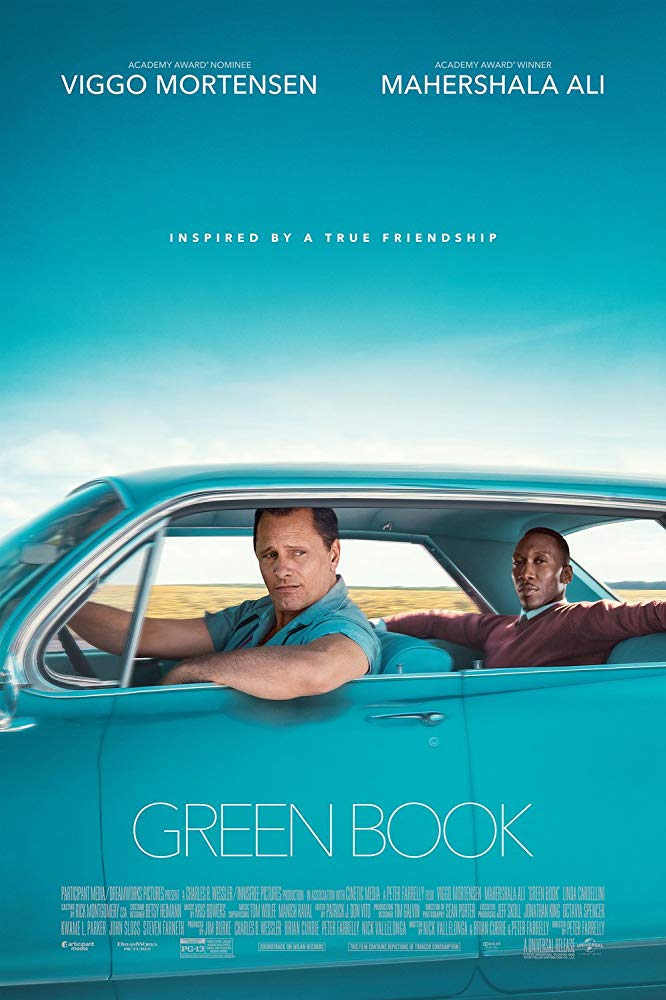

Similarly, in a realm where representation is the zeitgeist, the question of which film (out of Roma, The Favourite, Black Panther, BlacKkKlanksman, and Green Book) portrayed different social groups most effectively, lead each film to be analysed under meritocratic laws. Black Panther, while culturally significant, perhaps neglected film’s artistic side, while The Favourite and Roma neglected the industry’s popular side. One asks questions of BlacKkKlansman’s loss when, at once, the Academy had the chance to honour Spike Lee and address America’s racial climate. My supposition is that the film could be considered inflammatory in light of the country’s president, and the Oscar’s Republican members. Besides, they could nip it in the bud with an award for Best Adapted Screenplay. Similar appeasement was gifted to Roma three times, to The Favourite through best Actress, and to A Star is Born – which is certainly popular, but not artistic – through Best Original Song.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JPJjwHAIny4[/embedyt]

This is the culture of appeasement the Academy operates. Over twenty-four categories, there are plenty of opportunities to placate The Academy’s members and viewers alike, decentralising criticism from a concerted barrage of abuse. This year more than ever, the nominated movies, and the audience’s view of them, can be seen to have been addressed at least through acknowledgement, if not approbation.

Which leads me to try to comprehend the questionable success of Green Book. After #OscarsSoWhite, while it may do so clumsily (viewers of the film will discover that one of the text’s key lessons is that, hooray! Not all policeman are racist) Green Book is an example of subversive representation that is emotionally effective, with the addition of beautiful performances from the cast. That it is written by Nick Vallelonga, who’s islamaphobic views were published in a tweet that claimed Muslims had cheered at the fall of the twin towers, perhaps goes to mollify the other side. The award works to reward respected director Peter Farrely, too, who’s work on iconic movies such as Something About Mary remain award-less due to genre.

Green Book ticks a lot of the boxes for Best Picture; but the Academy’s decision to give it the gong was wrong. This year’s proceedings resemble an embarrassed child asked a maths sum in front of a jeering class. They say “this one? … this one?” to horrific screams of “No!” before their eventual point to “what about..?” is met with passive nods of “close enough”, despite it’s being incorrect. Such anxiety over decision will lead to similar missteps in the future, with most films winning something, and clean sweeps less likely. Spike Lee said that “the ref made a bad call”, and was right, but at least he got an oscar.