On Sunday 19 th March I logged off Twitter in a fit of frustration. This source of my indignation: once again Black Twitter was embroiled in diaspora wars. There are few places where seemingly disparate sections of the global black population are drawn together in cultural exchange, Twitter being perhaps the most significant virtual space to offer that, however occasionally those sites become battlegrounds where Caribbean islanders, African Americans, West Africans and Black British tweeters “fight” over which group is the most culturally relevant. Diaspora wars are often a mix of jokes, pettiness but sometimes they stray into harmful rhetoric.

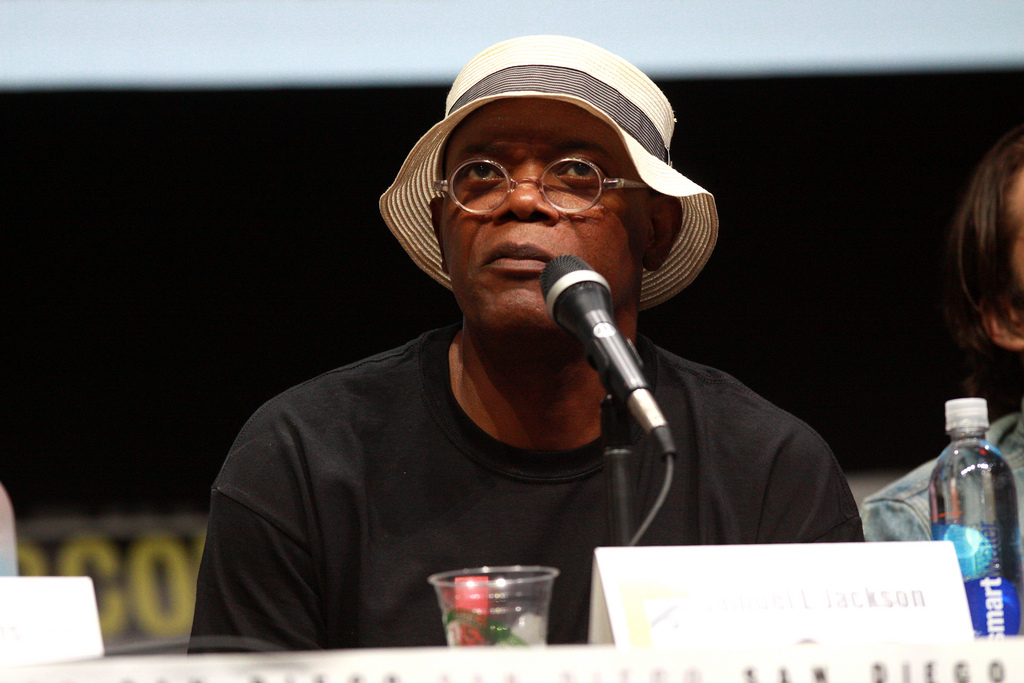

Tensions between Black Brits and African Americans flared up a few weeks ago after Samuel L Jackson made comments about roles given to black actors from the UK which he felt should be given to African American actors. He was referring explicitly to Daniel Kaluuya’s starring role in Jordan Peele’s thriller debut Get Out, but the comments also sparked discussion about roles portraying significant historical figures like Martin Luther King Jr, who was played by David Oyelowo in Selma.

Jackson and others suggested black actors from the UK cannot understand the nuances of pain and oppression felt by their African American counterparts and therefore shouldn’t portray them. What was particularly frustrating about Jackson’s comments for me was the ignorance it conveyed about the racial discrimination in the UK. In the “Diaspora Wars Uncut” podcast episode of 20something, Ogaga Emuveyan suggests that American knowledge of Black identity in the UK is limited: “we can see them and they can’t see us.”

From early childhood people in the UK are exposed to and submerged in American narratives, including representations of African American culture, history and media. The reverse is simply not true. American cultural imperialism means they have a far larger megaphone, so to speak, than black people in the UK or other western countries such as Canada. It makes it difficult to dispel the myth that the UK is some sort of post-racial utopia where we all communally sip tea and nibble crumpets, because experiences of racial discrimination are met with incredulity.

It doesn’t help that communities here thought not separated by oceans are still sometimes separated by antagonisms concerning culture. Tensions between the West African and Caribbean populations in the UK have been documented from as early into the beginnings of multicultural Britain as the 1950s, for example in Colin MacInnes’ City of Spades. However, I feel there has been of late a dissolving of those tensions thanks in part to Grime, where MCs of West African and Caribbean descent have continually collaborated. Call me cheesy, but I can’t help but see it as some sort of intra-diasporic embrace.

So it was both fascinating and frustrating that the release of Drake’s More Life, an eclectic mix of diasporic influences including Grime, seemed to cause both aural pleasure and cultural consternation. How dancehall-inspired is it really? Is this appropriation? Who the hell are Giggs and Skepta? Is UK rap just trash? That’s not to say we can’t have conversations about the rising influence of Grime, or the apparent lapse of America’s cultural dominance in certain places. That’s not to say we can’t have conversations about what counts as appropriation and what is appreciation. That’s not to say we can’t joke. Neither is it an issue of respectability politics concerning “fighting in public”.

It’s about the direction some of the rhetoric takes where it became less about the cultural exchange and more a thinly veiled fight about which group is “the best”. It’s ridiculous. What are the criteria for black cultural supremacy anyhow? How quickly the jokes became regurgitations of the same rhetoric utilised by white supremacy to denigrate black communities, a veritable showcase of internalised racism in the form of apparent “banter.” It’s all

irrelevant. There is a bigger fight. With the internet, even – for all its faults – with Twitter, has come something we lacked previously. We now have the chance to learn about each other in real time.

Americans have the chance to learn about the black British experience, black people in the UK British have the chance to learn about the Afro-European experience on the Continent. There are nuances to our respective struggles, but what it comes to ultimately is the struggle against white supremacy.

Image: Flickr